Category Archives: Adaptation

The Weight of Water (2000)

Kathryn Bigelow’s film The Weight of Water, based on the book by Anita Shreve, was released in 2000. The movie had been held back by the studio for over a year, and when it finally made it into theatres it sank like a stone. The few critics who reviewed it weren’t impressed. I remember that the night I first saw the movie the audience numbered less than ten. In fact, it might have been less than five.

So why did Bigelow, after directing a series of audacious and offbeat action flicks, decide to switch gears and film a very intimate novel about two women trapped in suffocating marriages? It’s a question worth asking, and I think there are probably a few answers.

One answer might be that she felt like a change of pace. Directors, like actors, can be afraid of getting type cast, and it may be that Bigelow wanted people to know she could do other things besides make action movies. Beyond that, though, it may be that she needed to do something that took her outside the confines of commercial formulas. While she’d managed to test the limits of the action genre, and even subvert some of its most basic rules, Bigelow understood that she still had to deliver what audiences wanted. Playing with the public’s expectations can keep them from showing up at the box office. Near Dark had been a modest critical and commercial success, but after that she ran into trouble. Nobody knew what to make of Blue Steel. Point Break made money but got trashed by critics. Strange Days got some enthusiastic reviews, but audiences stayed away. So Bigelow may have been wondering if she needed to take a break from action movies and try something different.

Another factor may have been the fact that Bigelow is a woman. I mostly avoid bringing up gender in writing about movies, because I think too often we fall back on easy stereotypes, sticking people in categories based on their sex. There’s no reason women shouldn’t be able to make action films, and Bigelow had proven her skill in the genre. But it’s a fact that the audiences for that kind of flick are mostly men, and those men have very specific expectations. I think the biggest reason her early features didn’t always go over well is that she was deliberately turning the genre on its head. A thriller centered on a female cop? Commonplace these days, but not back in the eighties. An FBI agent seeking spiritual fulfillment? Shouldn’t he just focus on shooting people? The audiences that flocked to Die Hard didn’t want movies to play with their expectations. They wanted massive explosions and a high body count. Bigelow may have gotten tired of trying to deliver what the boys were looking for.

But most important of all, I think Bigelow felt a powerful, personal connection to Shreve’s novel. It tells two parallel stories about women who are isolated and frustrated, angry and alone. Given the fact that Bigelow was one of the few female directors in Hollywood back in the nineties, it seems likely that she was experiencing all of the above. On top of everything, though, she was married to a director who also acted as producer on two of her films. Given that James Cameron was one of the most commercially successful filmmakers of the time, this might seem like a tremendous advantage. Really, I don’t think Bigelow saw it that way. At all.

It’s always dangerous to make connections between an artist’s work and their personal life. However close the parallels may seem, we have to remember that the work is fiction, not fact. Because of what we know about Woody Allen’s personal life, we may be tempted think that at times he’s actually presenting scenes from his life on the screen. This is a big mistake. Even if the episodes he’s acting out seem to echo incidents we’ve read about, we should never be so lazy as to think what we’re seeing is the “truth”. Art inevitably transforms reality. Allen may be incorporating autobiographical elements in Annie Hall, but Annie Hall is not an autobiography.

On the other hand, for me, a work of art is only worthwhile if the artist reveals something of his or her self. This may sound like a paradox, but it’s not. Who cares if the details depicted in a movie reflect the details of the filmmaker’s life. All that’s really important is that artists are honest about the way they see the world, the way they feel about themselves. We can speculate forever about possible parallels between Orson Welles’ actual life and the storyline of Chimes at Midnight, but in the end, none of that matters. What does matter is that when Hal says to Falstaff, “I know thee not old man,” we can feel the pain that’s crushing the new king’s former friend, and we know Welles felt that pain, too.

Anita Shreve’s novel The Weight of Water was inspired by a double murder that took place on a barren island off the Atlantic Coast at the end of the nineteenth century. A man was convicted and hanged for the crime, but speculation persists to this day that the jury sent the wrong person to their death. The book tells two stories, that of a young woman, a Norwegian immigrant, who relates the events leading up to the murders, and a modern story which focusses on a photojournalist who has come to the island to document the scene of the crime. Both the period story and the modern story are about relationships, both are centered on women trapped in unhappy marriages.

While Shreve’s book relates the known facts of the case, she makes it clear in a brief preface that it’s a work of fiction. The author creates a journal in which a young Norwegian woman named Maren talks about her youth, the pressures that forced her to take a husband, and the brutal challenges she faced after migrating to America, where she and her family are isolated on a remote, rocky island. The story that takes place in the present is centered on Jean, a photojournalist married to a famous poet. She loves her husband, but realizes his attention is straying, and the knowledge is slowly crushing her. As she investigates the Smuttynose murders, Jean finds Maren’s journal, and it’s clear she relates to the young immigrant’s desperation. They’re both just looking for a little affection, a little understanding.

Bigelow takes the fiction even further. Her film spends less time detailing the facts of the case and more time extending Shreve’s view of Maren as a deeply lonely, bitterly angry woman. In the book, the description of the actual killing is fairly brief. In the movie, the murders are crucial, and they are shown in terrifying detail. Like any filmmaker who uses historic fact as the basis for their work, Bigelow takes liberties to shape the story she wants to tell. Up to a point, I can accept that, but I’m not comfortable with showing a reenactment of a murder that’s based more on speculation than on evidence. Yeah, the film does offer a disclaimer, but it’s at the end, after we’ve seen a graphic depiction of Maren Hontvedt killing two family members. In reality, nobody knows who commited the crime.

It’s possible that the movie’s more visceral, graphic approach was the result of commercial considerations, but I doubt it. While I believe that Bigelow related to Shreve’s novel on a very personal level, as artists these two women are almost polar opposites. Shreve is a very careful, thorough writer who maintains a rigorous objectivity in her work. I have to say that I had trouble getting into the novel at first because the tone is so restrained. Gradually I was drawn into the world the author had created, both by her insight into human nature and the austere beauty of her prose. The book is really very moving, but Shreve always maintains a careful objectivity. She always keeps us at a distance from her characters.

Bigelow doesn’t keep her distance. As an artist and a filmmaker, she dives right into the world and drags us along with her. In her early films she used sound and image to create a voluptuous, kinetic experience, and at her best she pulled us right into the middle of it. Her characters were often thrown into situations where boundaries disappeared, and they’d find themselves caught between terror and euphoria. Though The Weight of Water is by no means an action film, again Bigelow’s protagonists find themselves pushed to their limits and beyond. In this case, though, the limits are less physical than psychological.

Here Bigelow uses her gifts to bring us into the characters’ state of mind. Jean sits on the deck of the yacht surrounded by placid blue water and crystalline vistas. The beauty and serenity of her surroundings are at odds with the tension that’s eating away at her. She watches her husband glancing furtively at the other woman on board the boat. She watches the other woman sliding a piece of ice down the length of her body. Seeing all this through Jean’s eyes, we know she’s just barely managing to hold herself together. The world Maren lives in, on the other hand, seems to be an expression of the melancholy she feels. The inside of her home is claustrophobic and dark. Within its oppressive quiet every small sound, the groan of the floorboards, the creak of a chair, is clearly heard. Even when Maren leaves the house, she’s still a prisoner on a barren island. There is no escape.

The script is extremely intricate, balancing the two stories against each other and weaving them together using deft, often abrupt, transitions. There are sudden shifts that may seem arbitrary, but actually the various threads are woven together with tremendous skill. Screenwriters Alice Arlen and Christopher Kyle make Jean’s investigation of the murders an exploration of her own troubled marriage. The more she learns about the case, the more she’s convinced that Maren is the killer, and the more she understands Maren’s motives.

And Maren’s motives are complicated. She goes about her chores dutifully, sticking to the routine that keeps her sane, but inside she’s drowning in a sea of conflicting emotions. She seems to have accepted her life of lonely drudgery, but the arrival of her brother and his wife creates new turmoil. The presence of Maren’s jealous, vindictive sister Karen makes life even more unbearable. Maren’s family isn’t a source of comfort. It’s a prison.

Bigelow is not credited as a writer, but I wonder how much input she had on the screenplay. The film sticks to the general outline of Shreve’s novel, but there are a number of alterations, some of them important. One change that strikes me as crucial is the fate of Jean’s husband, Thomas. At the climax of both the book and the film, the boat they’re on is battered by a terrible storm. In the book, Thomas survives. In the film, he dies. In my mind, I can’t help associating this choice with the break-up of Bigelow’s marriage to James Cameron.

And here I may be making the kind of assumption that I was criticizing earlier. How can I justify drawing a connection between something that was happening in the director’s personal life with a fictional event that she depicts on the screen? But honestly, I’m not trying to tell you that Bigelow wanted Cameron dead. And I’m not even trying to tell you that Thomas is a surrogate for Cameron. The way I see it, his death has a broader and a deeper meaning.

Earlier I talked about the fact that Bigelow was one of the few women directing films back in the nineties. While she had a few female allies in Hollywood, for the most part she was trapped in a system controlled by men. And whatever her personal relationship with Cameron was like, it had to be difficult making movies with your husband acting as producer. I think Bigelow’s choice to make The Weight of Water, at least in part, came out of a desire to change both the course of her career and the course of her life, to break away from the action genre and the limitations imposed by a male-dominated studio system. I think killing Thomas was a symbolic way of setting herself free, of burying the past. The more I think about The Weight of Water, the more it seems to me that the film is an exorcism. A way of casting out the demons.

While Bigelow’s earlier work had a spiritual dimension, it was usually in the background, easy to miss amid the shootouts and high-speed chases. In The Weight of Water, spirituality is right in the forground. In her misery, Maren feels cut off from God, and wonders why God has imposed this harsh, loveless existence on her. And while Shreve’s book outlines Maren’s religious beliefs in a general way, the film explicitly embraces a Christian perspective. The cross is used as a symbol throughout the movie, sliding across the screen in the title sequence, worn as a necklace by one of the women on the boat, cast as a shadow on a wall in Maren’s home. Bigelow is clearly exploring the Christian themes of suffering and salvation, asking difficult questions, and not necessarily expecting any answers.

The Weight of Water came and went very quickly. While Bigelow has enjoyed greater recognition than ever in recent years, this movie is pretty much forgotten. It’s certainly not for everybody, but it doesn’t deserve its obscurity. No question the film is a grim, sometimes harrowing, journey into the souls of two women who feel completely, desperately lost. But it’s also one of the director’s most passionate and personal works. Near the end of the movie Maren says, “I believe that in the darkest hour God may restore faith and offer salvation.” The Weight of Water is Kathryn Bigelow’s statement of faith.

Detour (1945)

The movie Detour has long been considered a film noir classic. Reams have been written about director Edgar Ulmer’s amazingly terse, unnervingly intense exploration of alienation and despair on the lonely stretches of the American highway. Ulmer was certainly a gifted filmmaker, and Detour is one of the high points of his career, but it’s odd that in the seventy years since it was made, almost nobody has talked about the novel it was based on.

The novel Detour was published at the end of the thirties, and in many ways seems to be a distillation of the period it was written in, the tail end of the Depression. Like Alex Roth, the luckless musician at the center of the story, author Martin Goldsmith had spent some time hitchhiking, no doubt getting well acquainted with hunger and hardship. The film’s screenplay is also by Goldsmith, and almost everything in it comes directly from the book. It’s an unusually faithful adaptation.

There are some major differences. In turning his slender novel into a surprisingly spare film, Goldsmith cut one of his characters almost entirely. While the book is framed by Alex’s story, starting and ending with him, the chapters he narrates alternate with chapters narrated by his girlfriend, Sue. The two met and fell in love working at a club in New York. Determined to become an actress, Sue left for Hollywood, postponing their marriage indefinitely. Desperately lonely, Alex decided to hitchhike to LA so he could rejoin his girlfriend. The book goes back and forth between the two of them, giving us an intricate portrait of their tangled relationship.

While Alex and Sue are basically decent people, they’re both driven to degrading acts by loneliness and lack of money. Goldsmith lets them explain themselves in their own words, and their stories are a mix of desperate self-deception and brutal honesty. Alex knows he’s basically a bum, but he can’t let go of the idea that some day he’ll become a successful musician. Sue realizes she’s just another star-struck fool scraping by as a waitress, but she keeps telling herself that somehow she’ll break through in Hollywood. They’ve both done things they’re not proud of and spend a good deal of time trying to justify their actions. Bottom line, neither one of them is perfect, and they know it all too well.

In the movie Sue is pretty much gone after the first reel. The screenplay gets her out of the way to focus on the poisonous relationship between Alex and Vera. This makes sense for a commercial feature, but it also makes the movie more conventional. Part of what makes Goldsmith’s book so interesting is the audacity of using a pulp thriller to dig into the maddening contradictions inherent in most relationships. Making Vera the central female figure brings the movie much more in line with the classic pulp framework, a more or less innocent guy dragged down by a scheming femme fatale.

Another interesting aspect of Goldsmith’s adaptation is the fact that he cuts out all of his rants about Hollywood. In the movie, pretty much all we see of Tinseltown is a series of rear projection shots, and the characters only refer to it in passing. In the book, the author spends pages describing his characters’ reactions to film capitol, and gives us a fairly detailed account of what it was like to live in the community at the end of the thirties. Goldsmith was living in Hollywood when he wrote Detour, and it’s clear that he was both horrified and fascinated by the place. His characters have wildly different reactions to what they see there. Alex arrives in Hollywood and likes it right away, describing how clean and sunny everything looks, admiring the people who look so healthy and tanned. But Sue, who works as a waitress because she’s had no luck with the studios, is bitterly angry that she was foolish enough to believe the hype. “I had arrived so thoroughly read-up on the misinformation of the fan magazines that it took me a full week before I realized that the ‘Mecca’ was no more than a jerkwater suburb which publicity had sliced from Los Angeles….”

The movie is just as relentlessly cynical as the book, but in a different way. Born in Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century, Edgar Ulmer was steeped in the northern European traditions of romanticism and expressionism. Before he started his career as a director, he had worked as a designer in stage and film, assisting Max Reinhardt, Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau. In making a film out of Detour, he brings a significant shift in emphasis. Goldsmith’s book is rooted in gritty reality, and in their moments of honesty the characters acknowledge that their lives were shaped by the choices they made. In contrast, Ulmer’s movie is about an innocent man whose life is completely derailed by fate. He has no choice. And there is no escape.

Ulmer spent most of his career working on low-budget and no-budget productions. At the time he made Detour he was under contract at PRC, possibly the cheapest outfit in Hollywood at the time. Most of PRC’s output was shot in six days and cut in one, an outrageously short schedule for making a feature film. In spite of these extreme limitations, Ulmer charges the movie with powerful imagery, making the visuals more striking and expressive than almost anything the major studios were doing at the time. Whether hitching a ride through the burning desert or brooding over a cup of coffee in a tiny diner, Al Roberts* is travelling through a dark psychological landscape. It often feels like the movie is taking place in his mind. Al is briefly enraged by a jukebox song that reminds him of his girlfriend. When he calms down again, the camera dollys in quickly to a tight close-up and the frame suddenly grows dim except for a small patch of light illuminating his eyes. Ulmer has no qualms about using a blatantly artificial effect to show the character’s emotional state. When Al stands over Vera’s corpse on the hotel bed, we see the room from his perspective, the camera panning slowly over various random objects, bringing them briefly into sharp focus, then allowing them to go hazy. We’re brought into the room with him, we share his feeling of stunned disbelief.

Another major difference in the movie is the way Vera dies. In Goldmsith’s novel, Al is so maddened by anger and fear that he strangles her when she tries to call the cops. It may not have been premeditated, but it’s definitely murder, and while Al is shocked by what he’s done, he doesn’t spend much time mourning. He runs. In the movie Vera’s death is definitely accidental. Having decided to call the cops, she grabs the phone, runs into the hotel bedroom and locks the door behind her. In total panic, Al grabs the cord and pulls with all his might, hoping to rip it out of the phone. Then he breaks down the bedroom door and finds Vera dead, the phone cord wound around her neck. There’s no knowing how this change came about. Did Goldsmith alter the scene on his own? Did Ulmer ask for something different? Was the production code a consideration? Whatever the reasons for the change, it definitely alters our perception of Al’s story. In the first version, he’s a murderer, even if he didn’t consciously choose to kill Vera. In the second version, he’s a helpless victim of forces beyond his control. After Haskell’s sudden death, Al’s chance encounter with Vera, and then her death in a freak accident, there’s no question that fate has taken a hand. He can run but he can’t hide. It’s only a matter of time before the darkness closes in.

Tom Neal has a forlorn charm that’s perfect for Al, an ordinary guy who’s trapped by an extraordinary set of circumstances. He just wants to get by, and at first he thinks everything will be okay if he just plays it cool. As things get worse and the pressure grows, Neal shows us Al’s nerves go from ragged to raw. He goes from ranting and raging to bargaining and begging, desperately trying to claw his way out of the mess he’s in. As Vera, Ann Savage burns a hole in the screen. It’s easy to believe that Al’s afraid of her. She’s a bottomless pit of anger and bitterness, and her intensity is scorching. But unlike the book, the movie gives us brief glimpses of another side of Vera. In her own way, she’s just as lost as Al. Vera’s led a hard life and probably doesn’t have long to live. In the few moments that Savage lets us see flashes of insecurity and desperation, it makes the character more than just another femme fatale. She seems vividly, pathetically human.

In the book, Alex manages to evade the law, but he can’t go home and he can’t go back to his girlfriend. He’s haunted by the memory of Sue, and tormented by the fact that his musical career has ended before it began. Goldsmith leaves Al stuck in limbo, bumming rides from one small town to another, earning a buck whenever he can. Still, he keeps moving forward. Life goes on. Ulmer’s ending is much more bleak. Al may have momentarily slipped free of the hangman’s noose, but he knows it’s only a matter of time before he’s caught. It’s not just bad luck that’s sent him on this detour. A mysterious force has singled him out, and there is no escape. When the highway patrol car pulls up alongside him at the end, he doesn’t struggle or try to run. He meekly steps inside. Because he knows it isn’t the police taking him down.

It’s fate.

——————————————————————-

*

In the book the character’s name is Alex Roth, but in the movie it’s changed to Al Roberts, no doubt because nice “normal” Anglo names were always preferred for Hollywood heroes.

Cabaret (1972)

Since the beginning of commercial cinema, filmmakers have been adapting stories that were successful in other forms. There are a few different reasons for this. Sometimes it’s just because producers feel safer investing in a property that’s made money for somebody else. But it may also be that a writer or director sees the possibility of bringing something new to a story, a way to reimagine it in another medium. And this is really crucial. If all you want to do is create a faithful adaptation, what’s the point? Making a movie just to illustrate somebody else’s work is a waste of time. A novel is an experience in words, and you can’t recreate that on the screen. It has to become an experience in image and sound.

Of course some stories migrate through many different forms before they reach the screen. Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin was published at the end of the thirties. It was an autobiographical novel based on his experiences living in Germany in the early thirties, when the country was falling apart and the Nazis were rising to power. Isherwood kept a journal during those years, and later used the material to create the novel. In it, he compares himself to a camera, passively recording what he sees, storing it for later, when he’ll have the time to develop and print the images. This is key to the way Isherwood approached his work. His novels are generally episodic, undramatic. Rather than trying to force life into a fictional framework, Isherwood was more interested in allowing life to unfold on its own.

This is an aspect of the author’s work that John Van Druten intended to highlight when he adapted Goodbye to Berlin for the stage and called it I Am a Camera. Actually, he focussed mainly on one part of the book, the chapter entitled Sally Bowles. Sally was a young English woman that Isherwood roomed with in Berlin. In most ways they were complete opposites, but for a while they became close friends. Sally was desperately searching for a rich man to marry while she halfheartedly pursued a career on the stage. In writing the play, Van Druten eliminated much of the book’s detail and gave it more structure, but he was faithful to the tone of the original. The passive young man at the center of the story is always slightly detached from whatever’s happening in front of him, always a little aloof from the hurly burly of life.

In the sixties, Harold Prince obtained the rights to both the book and the play with the idea of creating a Broadway musical. Joe Masteroff wrote a show that was loosely based on Van Druten’s play, with songs by John Kander and Fred Ebb. Cabaret opened in 1966, and was a solid success. It had even less to do with Isherwood’s book than Van Druten’s play did, but audiences loved it. A road show version toured the US, and in 1968 the musical opened in London.

It was only natural that Hollywood producers would take notice. And by the time Cabaret appeared on the screen it would be transformed again, moving even further from the book that Isherwood had written as a young man. Interestingly, the film version deleted some of the elements that made the show so successful on stage, and reached deeper into the characters. Jay Presson Allen’s screenplay fleshes out the relationships and spends a good deal of time exploring the decadence and violence that defined Berlin in the early thirties.

Looking at the film today, it seems like Bob Fosse is the only person who could have made it. At the time, the producers had other candidates in mind. Fosse had only directed one movie, Sweet Charity, which tanked at the box office, and he didn’t have much credibility in Hollywood. To their credit, the producers took a chance, and Fosse showed everybody how far he could go as a director. The film he made of Cabaret was a sharp break with tradition, and it had to be. The lavish song and dance spectaculars made by MGM in the forties and fifties had set the standard for the genre, but times had changed. Throughout the sixties the studios had been throwing money at bloated productions of Broadway musicals that sank at the box office. Somehow they didn’t understand that the audiences flocking to see M*A*S*H and Easy Rider didn’t care about Lerner and Loewe.

It wasn’t just Fosse’s skill that made him the right choice for the movie. The director was the son of a vaudeville entertainer, and grew up performing in burlesque. He’d made his way up the ladder, working in Hollywood musicals as a dancer and then as a choreographer. All his life, Fosse was immersed in show business, and show business was the lens he used to look at the world. Much of what makes Cabaret so thrilling is its unabashed theatricality. The numbers that take place at the Kit Kat Club grow out of what’s happening in the characters’ lives. In the novel and the play, we’re told that Sally sings in a cabaret, but we barely get a sense of who she is as a performer. In the musical and the film, her performances at the club become crucial, and, especially in the film, they comment on what’s happening in the world outside. This wasn’t a new idea, but in the past this device was almost always used to serve a romantic comedy plot. The people who brought Cabaret to Broadway used the songs as a mocking commentary on the corruption and the violence of the world outside, and Fosse pushed that even further.

The film Cabaret could have ended up being a brutally cynical spectacle that alienated audiences, who might easily have been offended by the way it turned musical conventions inside out. Instead, the film became a huge success, in large part because of its showbiz energy and its spectacular cast. Certainly Liza Minnelli was a big part of the equation. The role seems to have been written for her, and she plays it with a startling combination of vivaciousness and vulnerability. Offstage she has a capricious charm that wins us over. Onstage she has an energy and power that are overwhelming. Minnelli herself is a showbiz creature, and to a degree the role seemed an expression of who she was. While she’s been impressive in other films, Sally Bowles is still the part she’s most closely associated with.

As Brian, Michael York is at the opposite end of the spectrum, a mild-mannered young Brit who wants to write but for the time being supports himself teaching English. York’s low-key intelligence is the perfect foil to Sally’s over the top theatricality. And in spite of the chasm between them, the two actors make the relationship convincing. These two people are miles apart, but they still care about each other.

Joel Grey had played the role of the MC on Broadway to great acclaim, and it’s hard to imagine anyone else in the film. Strangely, Fosse resisted casting Grey and reluctantly agreed when the producers insisted. Grey’s performance isn’t just energetic, it’s ferocious. He gleefully throws himself into every number, unabashedly working the audience over, going as far as it takes to get a laugh or a round of applause. His intensity is scary, especially in the later part of the film as we see the threat of violence becoming a part of daily life in Berlin. The MC goes on grinning maniacally as the Nazis grow more bold, the brutality taking place on the streets slowly bleeding into the shows on the stage.

Fosse wasn’t the first director to pry movie musicals away from the traditional stagebound approach, but he uses cinematic devices in provocative new ways. He resorts to parallel editing a number of times, and each time with striking effect. Cross cutting from a knockabout stage show to a brutal beating on the streets makes the violence doubly frightening by underscoring the fact that the show just goes on even as innocent people are being assaulted. One of the most daring sequences is built around the song Maybe this Time. We see Sally alone on the stage under a spotlight, the accompaniment playing quietly in the background, and she begins to sing. But after the first line, Fosse cuts to a brief scene between her and Brian. Then back to Sally on stage, another line of the song, and then back to another short vignette. You’d think that interrupting the song would ruin the scene, but in fact Fosse’s approach heightens the tension and makes Minnelli’s performance even more powerful. Though you wouldn’t call Cabaret fast-paced, each scene flows seamlessly into the next. Editor David Bretherton shows a sharp sense of rhythm, and handles the complex dance sequences beautifully.

The film is visually dazzling, and no doubt a good deal of credit goes to cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth. Throughout his career, one of Unsworth’s trademarks was his sophisticated handling of light. We see the cheap boarding houses and the dingy cabarets through a sensual, erotic haze. But even as we’re being seduced by this divine decadence, the film will shove us up against the ugly realities of pre-war Berlin. In fact, one of the most interesting things about the movie is the way it keeps pulling us in, and then, without warning, punches us in the face.

Cabaret is very different from the novel that Christopher Isherwood had written thirty years before. But it had to be. Fosse and his collaborators looked at the book and the play and the musical, and borrowed from all of them, but created something new. It may be a story about Berlin in the thirties, but it became a success because it resonated with audiences in the seventies. And even if you’ve seen it before, it’s well worth watching again, because it still reflects the world we live in today.

The Trial (1962)

Orson Welles’ film of The Trial has never had a lot of fans. Many of his most ardent admirers have a hard time with it. Even Peter Bogdanovich, a champion of Welles’ work, has said he doesn’t like it. Aside from The Stranger, which the director himself dismissed, it’s the least popular of his movies.

Honestly, I’ve never understood why. The first time I saw The Trial I was completely drawn into it. It has a haunting, hypnotic quality. Watching the film gives me the feeling of being pulled slowly into another world, a strange, irrational world. No question the mood is oppressive, but to me this seems completely in keeping with the novel.

I disagree with the critics who say that Welles’ style is wrong for Kafka, but I understand what they’re talking about. Kafka’s prose is quiet, measured, precise. No matter what setting the stories took place in, to me his world always seemed small and claustrophobic. But in the film Welles’ creates vast, echoing spaces, and long, twisting corridors. The characters have a different presence, too. Kafka sketches the people who populate his world in a very few, deft strokes. Welles, on the other hand, draws them in vivid detail.

But while the two men’s styles are totally different, I think the film comes very close to capturing the essence of the novel. The writer and the director may seem like polar opposites, but they’re not. In Welles’ films the heroes are often brash and arrogant, fighting to impose their vision on the world. In Kafka’s stories we wouldn’t even use the word hero to describe the protagonists, because his anxious, insecure young men are constantly struggling just to keep moving forward. Still, if we look deeper, we might find that the two have a lot in common.

When I first read Welles’ comment that The Trial was his most autobiographical movie, I was surprised. How could this man, who seemed so much larger than life, identify with the weak, petty Joseph K.? But anyone familiar with Welles’ career knows that he worked very hard to create the magnificent mythology that defined his public persona. In fact, for the most part his work is about exposing the lies behind the myths, showing us that these “great” men are deeply flawed.

Behind all the bravado, Welles was terribly insecure. Ignored by the mainstream audience, frequently attacked by critics, begging for money from backers, acting in films he knew were beneath him, he must have often felt very lost and very lonely. And if we look at the comments he made throughout his life about the injustices perpetrated by our governments and the growing tyranny of bureaucracy, his concerns begin to seem much closer to Kafka’s. He begins to seem like a man who feels completely overwhelmed, living in a world that’s indifferent to his existence.

After the prologue that starts the movie, the first image we see is disorienting. Joseph K.’s face upside down as he lies asleep. Waking up, he finds strange men in his room. Angry and confused, he demands an explanation, which they give him. He’s been accused of a crime. They’ve come to investigate. K.’s anger and confusion turn to fear and anxiety. Welles thrusts us into this bizarre, uncomfortable situation at the very beginning, and for the rest of the movie he just keeps pulling us deeper and deeper.

The Trial sounds different from any other film I can think of. Much of it is very quiet. Sometimes the actors’ voices seem to sink into the silence. At other times they resonate in space, echoing off surfaces of concrete and metal. Welles often used post-synched sound, and while this could sometimes be a handicap, here it’s eerily right. It feels as though there’s a slight distance between the actors and their voices, adding to the sense of disorientation. Throughout the film, Welles uses sound to keep us on edge. From the deafening din of a thousand typewriters to the silence of an empty street at twilight. From the nasty chatter of a crowd of wild girls to the frantic clatter of footsteps careening down a corridor.

Anthony Perkins is perfectly cast in the leading role. K.’s rapid shifts from arrogance to anxiety could easily make the character tiresome, but Perkins brings a vulnerability to the role that makes him seem human. I guess a lot of people have trouble relating to the character, but I can totally identify. Is there anyone out there who hasn’t felt like they were battling to stay sane in a crazy world? Jeanne Moreau is stunning in the small role of Fräulein Bürstner, a world-weary bar hostess who shuts K. down with her icy indifference. As Leni, Romy Schneider vibrates with a kinky erotic charge. She’s both seductive and scary. With his usual consummate skill, Akim Tamiroff disappears completely into the role of Block, a pathetic, fawning businessman whose life has been consumed by pleading his case. Welles had a high regard for Tamiroff’s talent, putting him in key roles in four films. And, of course, there’s Welles himself as the Advocate. Apparently he only took the role because his first choice, Jackie Gleason, dropped out, and he couldn’t come up with a suitable replacement. I can’t imagine anyone else in the part. Welles plays the scenes in the Advocate’s bedroom for chilling comedy. Later, during the final dialogue in the cathedral, he’s just chilling.

I have to admit, the ending is a problem. The last exchange between K. and the Advocate in the cathedral was mostly written by Welles. This is where the director departs from Kakfa. In the film, K. rejects the idea of a world without meaning, without hope. He insists that he’s a member of society, and that implies responsibility. He won’t accept the madness imposed by the system. This is the complete opposite of Kafka’s world, where the author’s characters inevitably submit to their fate. In the book, K. dies at the hands of his executioners.

Welles couldn’t accept that. He said in interviews that he believed Kafka would not have written such an ending if the author had lived to see the Holocaust. After the death of six million Jews, Welles could not allow K. to surrender to the system. He felt it was necessary to make a more affirmative statement.

But that left him with a huge problem. Welles knew that he couldn’t give the film a “happy” ending. It wouldn’t have been true to Kafka, or to his own world view. Welles has K. take a stand against the system that’s working so hard to grind him down, but to end the film with some simple triumph would be too easy. And so he gives us an ambiguous conclusion, which doesn’t really work.

Even with my reservations about the end, I still think the film is pretty astonishing. Welles conjures up a frightening vision of the modern world, dominated by an endless bureaucratic maze. He follows K. through the grim landscape of Cold War era Europe, the arid modern apartment blocks and the voluptuous ruins of the past. It may be difficult to watch because it shows a side of the director we’re not used to, a side that maybe we’d rather not see. We’re used to seeing Welles play the supremely confident showman, a larger than life figure who dominates every situation. But if Welles was being honest when he called The Trial his most autobiographical film, then maybe he’s offering us a different, more candid, self-portrait. A portrait of a frightened, insecure little man who’s afraid the world will swallow him completely.

De noche vienes, Esmeralda [Esmeralda Comes by Night] (1997)

Elena Poniatowska’s work is part of the fabric of modern Mexico. In her non-fiction she’s dealt with the traumatic events that have shaped the nation, and in her fiction she’s been a sharp critic of her country’s culture. Her short story De noche vienes is a humorous attack on the hypocrisy surrounding sex and marriage in Mexico (and elsewhere). A woman is charged with bigamy when it’s discovered that she has five husbands. The official interrogating her is shocked at her behavior, insisting that her actions are an attack the very foundation of civilized society. What shocks him most, though, is the fact that she feels no shame about marrying five different men. They love her. She loves them. She accepted their proposals because they all seemed to need her.

Jaime Humberto Hermosillo’s film, De noche vienes, Esmeralda, expands on Poniatowska’s short story, filling out the characters, embroidering the situations, but staying close to the author’s original intent. He makes it a modern day fairy tale, and at the center is the innocent heroine, whose only sin is that she doesn’t feel guilty about sleeping with five men. Hermosillo does alter Esmeralda’s motivation. In Poniatowska’s story, she feels it’s her duty to help those in need. Getting married five times is her way of helping these five needy men. In the film, Hermosillo explains Esmeralda’s behavior by making her a product of the culture she lives in. Since childhood she’s been led to believe that sex without marriage is a sin. When she opens her closet we see the door is covered with photos from her weddings, and in each picture she’s dressed in immaculate white.

The other thing Hermosillo does is expand on the theme of sexual freedom. The original story stays with Esmeralda and the judge, and we never get to meet her husbands. In the movie we meet all five of them, and we learn that most of them are pretty open-minded about sex. The first husband is an older man who knows he can’t keep up with her in bed, so he accepts that he’s not the only man in her life. The second is a musician, and Esmeralda realizes early on that he’s sleeping around. Another is gay, and in this case she’s helping him hide that fact from his mother. The judge may see her behavior as promiscuity, but it’s really just generosity.

The premise may seem far-fetched, but María Rojo acts the part of Esmeralda with such conviction that the character is completely believable. She doesn’t just play innocence, she radiates it. The judge does everything he can to shame her, and she seems oblivious. She answers his questions with total honesty, a beatific smile spreading across her face when she thinks of how much she loves her husbands. Rojo gives the character such warmth that she wins us over completely.

Claudio Obregón has the difficult job of making us believe that the cranky, uptight judge could slowly melt into one more of Esmeralda’s smitten suitors. He makes the transition totally convincing. Martha Navarro and Antonio Crestani both give ingratiating performances as court employees who quickly find themselves on Esmeralda’s side. Roberto Cobo brings a wonderful sweetness to the role of the aging poet that Esmeralda married on what seemed to be his death bed. And Tito Vasconceles is a joy to watch, popping up over and over again in numerous guises as Esmeralda’s guardian angel.

Hermosillo doesn’t create images so much as he creates scenes. He tends to use long takes, allowing the actors to develop a situation, and the camera slowly roams around them. For the most part, this relaxed, leisurely approach works well, but there are times when I think the structure could be tighter, and that Hermosillo could provide more focus. On the plus side, by not cutting to impose his own pace on the scenes, the director allows the actors to really get into their roles. They can find their own rhythm, and develop relationships in their own way.

The director references Juana de Asbaje and Frida Kahlo, two Mexican women who also broke the rules, and it might be tempting to see the film as an argument for women’s liberation. Certainly you could see Poniatowska’s story that way. But Hermosillo is after something broader. He wants to liberate everybody. In his mind the whole world is held prisoner by guilt and shame. And his message is, you have nothing to lose but your chains. At the end of the film, the judge confesses his love for Esmeralda, and after she encourages his advances, he goes dancing down the street in the rain. He’s let go of his hang-ups. He’s a free man.

The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death is a brief, terrifying parable. Prospero is a wealthy prince whose land is being ravaged by a plague. He gathers his aristocratic friends together in a castle and seals it tight to keep them all safe from the disease. Believing that they now have nothing to fear, Prospero and his guests devote all their time to extravagant entertainments, while those left outside face certain death. But like a story in the Old Testament, The Masque of the Red Death ends in terrible retribution. Prospero and his friends learn that no walls are thick enough to save them from the plague.

When I went back to story and re-read it, I was surprised to find that Prince Prospero is the only character mentioned by name. Poe spends little time describing the man himself, and he only speaks a few lines of dialogue. Most of what we learn about Prospero comes through the author’s description of the apartments designed by the prince, a suite of seven rooms, each decorated in a single color and lit by torches that shine through colored glass. The scene that Poe paints for us is highly stylized, almost abstract. Really it’s the landscape of the mind.

To make a feature length commercial film, director Roger Corman obviously had to flesh out the material. This can be a dangerous proposition, because often the whole effect of a short story depends on its brevity. But Corman was a lifelong admirer of Poe’s work, and he knew that he couldn’t just add padding to the author’s tale. The screenplay would have to expand on the material in such a way that it grew organically from Poe’s original concept.

Corman has said that in his Poe adaptations his preferred approach was to use the original story as the third act, the climax of the film. That’s what he does here, and the screenwriters do a beautiful job of fleshing out this macabre little tale. The script, by Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell, expands on Poe’s story a good deal, and yet it stays essentially faithful to the author’s conception. In addition, Beaumont and Campbell bring in fragments of another Poe story, Hop-Frog, weaving it skillfully into the framework of the film.

What the screenwriters do with Prospero is pretty impressive. Starting with the minimal details that Poe offers in the story, they create a fascinating, multi-faceted character. This is not your standard horror movie villain. Prospero is a philosopher who sees the world in the bleakest possible light. He is horribly cruel, but he is also intelligent, thoughtful and sensitive. This is a man who has spent his life observing the world, seeing the horror and misery that plague mankind, and he has become brutally cynical. He refuses to believe in a loving God, because he can’t believe that God would allow the suffering and the violence he’s witnessed.

As the film begins, we see Prospero’s cruelty in the harsh punishments he inflicts on the peasants in a small village. But as the story unfolds, we learn that he has no more respect for his fellow aristocrats than he does for the peasants. He sees his guests as weak and foolish, and he takes joy in humiliating them. He’s appalled by humanity. It’s as though he’s punishing mankind for its cowardice and stupidity.

Prospero is a frightening, fascinating character, and the part would be a challenge for any actor. Fortunately, Corman turned to Vincent Price, who he’d already worked with on a number of films. Price is magnificent. His performance is a marvel of intelligence and subtlety. Prospero is repellent, and yet at the same time we can’t take our eyes off him. Playing the part, Price commands our attention, but without unnecessary theatrics. Graceful and witty, cold and merciless, the actor’s performance as Prospero is one of his finest.

Art director Robert Jones and production designer Daniel Haller create an oppressive, expressionistic world that reflects the disturbing beauty of Poe’s writing. A young Nicolas Roeg shoots it all with striking confidence. The richness and subtlety of Roeg’s lighting gives the images dimension and depth. By this point in his career Corman was very assured as a filmmaker and he seems to have an intuitive understanding of the rhythm and shape of a scene. His camera glides through the chambers of the castle, settling on one composition, shifting to another, defining the relationships between the characters and heightening the tension.

Sound also plays an important part. Striding through an eerie silence, Prospero lectures his guests on the terror of time, the ticking of a clock in the background, the soles of his shoes clicking against the marble floor. Francesca is wakened in the middle of the night, and as she peers through the dark bedroom we hear the flutter of birds’ wings receding into the night, suggesting a phantom in flight. In keeping with the way Poe uses words, Corman uses images and sounds not just to create a physical world, but also a psychological landscape.

I often hear people make excuses for crude, shabby horror movies. They didn’t have the money. They didn’t have the time. Roger Corman proved over and over again that limited resources are no excuse. With a little creativity and cunning, a filmmaker can work wonders, even if they’re shooting on a shoestring. It’s not the size of your budget. It’s the size of your imagination.

Moby Dick (1956)

You really can’t put a book like Moby Dick on the screen. There’s no way to duplicate the experience of reading Melville’s words and being drawn into the ecstatic chaos and the terrifying poetry of his world. But John Huston was never one to shy away from a challenge, and in fact, he seems to have enjoyed taking on projects that tested him. If his version of Moby Dick isn’t completely successful, it’s still a beautiful and powerful adaptation that preserves much of what was most important in the book.

One of the problems in making a commercial film from Moby Dick is that it’s less a novel than a cosmic meditation on God, man and nature. There’s very little plot. At the beginning an innocent young man gets on a boat with a crazed captain in search of a white whale. At the end they find the whale, the boat is destroyed, and the young man is left floating in the middle of the ocean. In between, Melville’s narrator, Ishmael, offers his musings on life, death, the ship, the sea, and endless ruminations on whales.

Huston hired Ray Bradbury, who at that point had never written a screenplay, to fashion a script from the book. While the two men had great admiration for the other’s talent, apparently they didn’t get along at all. The experience was a traumatic one for Bradbury, but for the most part Huston was very pleased with his work, and the finished product gave the director an admirable adaptation to start with.*

There are moments in the film that capture Melville beautifully, and one of them is the opening sequence where we see Richard Basehart as Ishmael, strolling through the countryside, following the course of the water as he makes his way to the shore. Basehart was the perfect choice for the central character. He keeps us with him all the way, Ishmael playing the fascinated witness to Ahab’s monstrous madness. Basehart is surrounded by a marvelous supporting cast. On his arrival in New Bedford, the young sailor is greeted by Stubb, and Harry Andrews plays the veteran seaman with a vigor that is both intimidating and ingratiating. Orson Welles delivers Father Mapple’s sermon about Jonah with a sober gravity and a heartfelt humility that serves as the perfect prologue to this story of a man who dares to defy God.

Many people have criticized Gregory Pack’s performance as Ahab. Huston defended Peck, and I have to say I side with the director, though with some reservations. I think Peck has all the steely resolve that Ahab should have, and he is convincingly commanding as the captain who seduces his crew into following him to the gates of hell. On the other hand, I feel that there’s a certain weight or depth that’s missing. I don’t know if I would say that Peck is miscast. The role must be incredibly difficult to play, and there are probably few actors who could really take it all the way.

Opposing Ahab is Starbuck, and Leo Genn plays the part with impressive conviction. Starbuck is the voice of morality, a humble man who believes that in doing their work the whalers are serving humanity and serving God. Genn does a fine job of portraying the chief mate’s conflicted feelings as he slowly realizes that the captain has no interest in anything except pursuing the white whale. Starbuck is a Quaker, but he is so deeply disturbed by his captain’s conduct that he finds himself contemplating mutiny, and eventually murder. It’s a striking performance that’s easy to overlook, because the actor is so completely immersed in the role.

Oswald Morris, the tremendously gifted cinematographer who shot the movie, says that Huston wanted to recreate the look of nineteenth century steel engravings. After extensive tests, Morris hit on the idea of desaturating the color image and adding a grey image over it. This approach imbues the film with a dark beauty, giving the sailors’ faces, the weathered boat, and the glowering sea a grim, storybook look. The score by Philip Sainton is good and supports the drama well, but it is the source music, the various songs sung by the crew and the townspeople, that bring us into this peculiar world of whaling towns, whaling boats and whaling men. There is the wild dance at the New Bedford inn, accompanied by a boisterous accordion. There is the solemn hymn sung by the church’s congregation as the prelude to Father Mapple’s sermon. And there is the ringing chant that the whalers shout out as they row steadily towards murder or death. This is the music that these people sing in celebration and in sorrow, the music that is woven into the fabric of their lives.

Huston does a magnificent job of portraying both the wonder and the terror that must have been inextricably intertwined on a nineteenth century whaling ship. The director was an adventurer himself, and was constantly searching for projects that would challenge him and challenge his audience. This didn’t always work out. It’s not easy to combine action with introspection, especially when you’re shooting on the ocean in bad weather and the budget is spiraling out of control. I feel like the final sequence, the whalers’ attack on Moby Dick and the murderous revenge he takes on them, goes by too quickly. Huston has written about the extreme difficulties that his crew had filming at sea, and it’s possible they couldn’t get all the footage they needed.

In the end it doesn’t matter whether Huston pulled it off completely. At its best the film is so rich and so powerful, so subtle and so complex, that it seems foolish to complain of its faults. Most commercial filmmaking is based on familiar formulas because it’s easier to turn a profit when you play it safe. Huston didn’t play it safe. He was always ready to take a chance, and often found himself out on a ledge, dancing on the brink. For an artist, that’s not a bad place to be.

————————————————————————————-

*

Years later Bradbury wrote a short teleplay titled The Banshee, which is based on his stormy relationship with Huston. It’s both creepy and funny, and Peter O’Toole is devilishly perfect as the autocratic director, whose name happens to be John.

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939)

It’s important to start by saying that Anderson’s version of events was not historically accurate, and that Warners’ took further liberties with the facts. What makes the play so compelling is the way the author digs into the two central characters, ripping away the layers of pride and pretense as Elizabeth and Essex battle for control of the relationship and control of England. The screenplay, by Norman Reilly Raine and Aeneas MacKenzie, discards much of Anderson’s dialogue and completely alters the structure, but actually ends up being nearly as complex and involving as the original play. The film is surprisingly literate for Hollywood, and what’s even more surprising is that the screenwriters manage to create a historical love story that is lively and interesting.

The film goes far beyond the narrow emotional range of most Hollywood films, and Curtiz is up to the challenge. He understands the possibilities in the material and uses his considerable gifts as a filmmaker to dramatize the screenplay. While the background is brimming with pomp and pageantry, in the foreground we see two people who are intelligent and passionate, vain and insecure, struggling to come to terms with each other. Art director Anton Grot creates spaces both vast and intimate, using vibrant color to set the emotional tone for each scene. Cinematographer Sol Polito finishes the job beautifully with his fluent use of light and shadow.

The heart of the film is Davis’ performance, and she is amazing. She was clearly fascinated by Elizabeth, and her commitment to the part is obvious. Her performance has nothing to do with Hollywood’s standard notions of romance. Her Elizabeth is not attractive or seductive. She does not try to ingratiate herself to us in any way. Davis plays the queen as a brilliant and neurotic woman, desperately wanting to be loved and absolutely determined not to show it.

Flynn, on the other hand, plays Errol Flynn. It’s not that he’s bad, but his performance isn’t in the same league as his co-star’s. He brings the same level of commitment to this role as he did to Captain Blood or Robin Hood, but the script demands more. He handles the dialogue well enough, but his performance is all on the surface. It’s possible that at this point in his career Flynn couldn’t dig any deeper. But the rest of the cast is solid, and there are a few standouts. Apparently the experience of making the film was traumatic for Olivia de Havilland, but she is excellent as Penelope. The role gives her a chance to step away from the wholesome, good girl image that Warners had forced on her. And Donald Crisp plays Francis Bacon with impressive skill and subtlety.

The adventure films that Flynn and Curtiz made all have simple, clear stories that outline a basic struggle between good and evil. Though they’re ostensibly about heroism, for the most part they’re really about exploiting our childish desire for reassurance. The leadership at Warners made an effort to fit Elizabeth and Essex into that mold, but the basic premise of the film defied that kind of simplification. Though not historically accurate, it’s a real story about real people and real human failings. We are made to see that the brave and dashing Essex is a vain, impetuous egotist who understands little about the realities of running a country. And we can’t even fully sympathize with Elizabeth, who is a jealous, neurotic egotist willing to sacrifice the man she loves to retain her power. It’s the antithesis of the standard formula, because it shows how empires are really built. And there’s nothing reassuring in the outcome.

*

I’ve been interested in art director Anton Grot’s work for a while. He worked on many films with Curtiz, and is credited on numerous other Warner features in the thirties and forties. It’s been really hard to find information on Grot, but I did come across a blog which features several of his drawings. As far as I can tell, most of them were done for Captain Blood, but it looks like at least one was for Mildred Pierce, and the last one is probably for Elizabeth and Essex or The Sea Hawk (the two films share a number of sets). If you’d like to check the drawings out, click here.

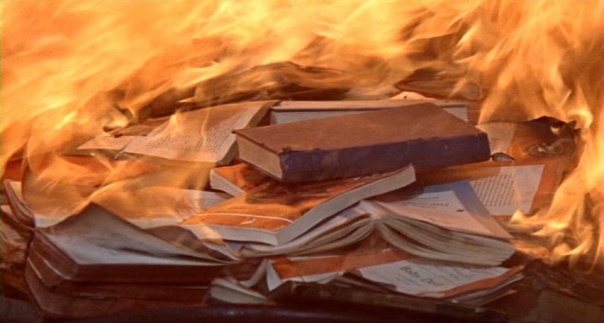

Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

When a director sets out to turn a book into a movie, they have to make it their own. There is no way to take words on a page and translate them literally into images and sounds. Even if a filmmaker didn’t have to deal with the time constraints of a commercial feature and had the freedom to include every event, every episode described in a novel, there’s no way to replicate the experience of reading a book on the screen. They’re two different mediums, and to make a successful adaptation, you have to transform the book into a film.

So I can’t really fault Francois Truffaut for not capturing the feeling of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in the film he made of the novel. Bradbury’s work is so much about the experience of words, and the resonance that words have, there’s no way you could replicate what he does in a movie. But I still have to say that the film doesn’t work for me. I’ve never been able to connect with it.

Which is not to say that it isn’t worth watching. In many ways I think the film is kind of brilliant. The world Truffaut creates and the visual language that he uses have a striking immediacy. While his earlier features were shot largely on location, Fahrenheit 451 was made in a studio. Truffaut uses this to his advantage by emphasizing the artificiality of the environment that Montag, the fireman, lives in. Art director Syd Cain (aided by Tony Walton, uncredited) gives an eerily bright, hard-edged look to this future society where TV controls all information and conformity is the key to survival.

The brilliant reds and solid blacks of the fireman’s world contrast effectively with the earth tones of the natural landscapes and the homes inhabited by the book people. Cinematographer Nicolas Roeg takes full advantage of these extremes. He is amazingly sensitive to the various qualities of light, using it to define the stark, modern interior of the firehouse, and to paint the subtle, ghostly beauty of the English countryside. Working with editor Thom Noble, Truffaut finds a rhythm to suit each sequence. Jump cuts give urgency to a scene where a man is warned he’s about to be busted. The firemen’s raids crackle with a scary energy. Long, uninterrupted takes emphasize the arid, sterile atmosphere of a suburban home.

But in spite of all that, I have to say I just don’t connect with the film on an emotional level. There’s something strangely detached about it. You might say that the movie’s polished, impersonal feel would be totally appropriate for this cold future world, but if we can’t connect with Montag as he struggles to break free, then there’s no dramatic impact. As creative as Truffaut and his team are in giving the film a look and a feel, for me the finished product is emotionally flat.

Pauline Kael felt Truffaut’s approach was too restrained, and she may have a point. Fahrenheit 451 was one of Bradbury’s early novels, and it clearly comes out of his roots as a pulp writer. Apparently the book was the author’s response to the chilling oppression of the McCarthy era, and the theme of an individual struggling against a totalitarian government could hardly be stated more bluntly. Montag has to choose between good and evil. Truffaut may not have been comfortable with such a clear-cut moral choice, and he seems unwilling to play it to the melodramatic hilt. There is a reserve in his approach which makes the actors seem strangely distant. It’s also possible that, since this was his first film in English, the language was a barrier he couldn’t quite overcome. And it’s important to mention that the director’s relationship with Oskar Werner was strained during the making of the film, which may have affected the way Montag comes across, or doesn’t come across.

Then again, a good deal of what makes the book memorable is the language, and that’s something you can’t put on screen. I started to re-read Fahrenheit 451 recently after watching the film. I have to say that the story does seem naive and melodramatic. I definitely feel like it’s the work of a young writer, and it doesn’t have the depth or the subtlety of the author’s later work. But the way he writes is totally compelling. Bradbury’s language is dense, rich, intoxicating. His prose is so close to poetry that the line between the two disappears. There’s poetry in Truffaut, too, but it’s a different kind. As a filmmaker he seemed to be seeking clarity, simplicity. Often his best films, such as The Wild Child and The Story of Adele H., have a brusque directness, a naked honesty that allows us to get very close, often uncomfortably close, to the characters. The poetry is held in check, never being allowed to overwhelm the story. Bradbury, on the other hand, wants to overwhelm the reader. He plunges us into his own sensual dimension, a world of experiences he describes so vividly we can touch them, taste them.

While Truffaut’s sensibility is different from Bradbury’s, composer Bernard Herrmann is very much on the writer’s wavelength. His score has a rapturous intensity that is completely in tune with Bradbury’s world. Herrmann sets the tone with the first cue. As a narrator recites the credits over images of TV antennas, strings playing ethereal, shifting harmonies with no resolution, preparing us for the film’s chilling vision of the future. Immediately after we’re assaulted by the bracing, dissonant music that accompanies the firemen’s raids. Throughout the film, Herrmann’s eerie, otherworldly score keeps us off balance with its strange harmonies and unusual rhythms. It’s only at the very end, when we’re in the forest with the book people, snowflakes drifting from above, that the composer introduces a lovely, lilting melody, letting us know that Montag has finally found safety. The tension and anxiety that have dominated the score are gone, and the final, resounding chords reassure us that there is hope.

So while I’ve got some serious problems with the film Truffaut made from Fahrenheit 451, I also find a lot to like in it. I get the feeling that the director was trying to challenge himself by taking this project, a far cry from Shoot the Piano Player or Jules and Jim. It also seems like he was trying to assimilate what he’d learned from Hitchcock, not just in this film but in others like The Soft Skin and The Bride Wore Black. While I’m not crazy about his work from this period, I think it was important for him to explore this approach. Artists have to make mistakes to grow. We all do. As Buckminster Fuller said…,

“How often I found out where I should be going only by setting out for somewhere else.”

The Breaking Point (1950)

Anybody who’s a fan of movies from the studio era probably has a soft spot for Howard Hawks’ To Have and Have Not. It’s hard to beat for sheer entertainment, taking full advantage of its charismatic stars and a top-notch supporting cast. It’s also totally superficial. We know from the start that the good guys are going to win and that Bogart is going to walk off with Bacall. It’s a classic example of the way the studios would take a book and transform it into something almost unrecognizable. In the case of Hemingway’s novel To Have and Have Not, Hawks took the premise of a guy on a boat in the Carribean and dumped everything else.

Really, he had to, because the original novel is extremely unusual and brutally cynical. Actually, I think the book is pretty interesting, but its fragmented narrative and strange digressions pretty much defy all the conventions of commercial filmmaking. On top of that, it was wartime, and the studios were determined to keep everything upbeat and positive.

But by nineteen fifty things had changed. There was a strong undercurrent of cynicism running beneath Hollywood’s glamorous surface. People were making films that not only questioned the status quo, but suggested that we were living in a world where the deck was stacked against us. That’s pretty much the thrust of Hemingway’s novel. The book is about those who have money and those who don’t. And the conclusion that the main character reaches by the end is “A man don’t stand a chance.”

According to Eddie Muller, it was John Garfield who suggested doing a remake. Screenwriter Ranald MacDougall was brought on board to do the adaptation. Though he moved the story into the present and changed the location to Long Beach, it’s much closer to both to the letter and the spirit of the book than the Hawks version. Harry Morgan is a fisherman struggling to support his family and hang on to his boat. The story shows how he’s driven to ever more desperate measures to make money, finally agreeing to take part in a robbery.

Garfield’s gripping, lively performance is the heart of the movie. Harry starts out as a fairly easygoing guy who just wants to make a living, but as he feels the screws tighten we can feel him tighten up as well. Garfield had a gift for playing average guys, and did it without sentimentalizing his characters. He doesn’t ask for our sympathy, he just plays the role as honestly as he can.

Harry loves his wife, and he works hard to provide for her and the kids. Lucy Morgan loves her husband but she’s slowly getting ground down by the stress of making do with almost nothing. Phyllis Thaxter plays the part with admirable simplicity and sublety. The one character that’s borrowed from the Hawks version is the sexy drifter, who in this case tests Harry’s commitment to his wife. The role was probably created to make the movie more commercial, but Patricia Neal is so good that it’s hard to complain. She’s tough, smooth, cynical, and still vulnerable in a way that makes her seem human.

Those who are mostly familiar with Curtiz’ polished films of the forties might be surprised by the gritty intensity of The Breaking Point. It has the energy and the tension you can find in some of his thirties melodramas, but here the characters are more complex. Curtiz keeps his camera close to the actors, and MacDougall’s script allows them to dig into their roles. We have no trouble believing that they inhabit this world, that their lives are rooted in this small seaside town. Cinematographer Ted McCord is amazingly sensitive to the ways in which light can define a location and the subtle nuances of mood it creates. He makes a working class kitchen and a waterfront bar equally real and vivid. Whether he’s shooting on location or on a soundstage the images have the same attention to texture and the same vibrant immediacy.

At the end of the film Harry has survived a shootout with the robbers, but it looks like he’s going to lose his arm. Delirious, he rambles on about how “a man don’t stand a chance”, but calms down when his wife arrives. She convinces Harry to let the doctor amputate, and she’s with him as they carry him to the ambulance. Not the happiest of endings, but we feel a sense of hope. Then the camera pulls back and we’re left with the final startling image. Harry’s sometime partner Wesley was killed in the shootout. As Harry and his wife, the police and the doctors exit the frame, we’re left with a shot of Wesley’s young son standing by himself on the pier. This image of a child, alone and forgotten, is the film’s most powerful moment. It’s totally unexpected, and the movie is over before we can absorb it, but it lingers in the memory. Hollywood movies generally end with the promise that everything’s going to be all right. The Breaking Point does not, and it’s all the more powerful because of its honesty. It tells us that everything is not going to be all right.