Near Dark (1987)

A young man and a young woman are running through a deserted industrial area. The sky is a sheet of black, lit only by dim yellow orbs hanging overhead. The woman stops, and raises her hand.

‘Look. The night. It’s so bright it’ll blind you.’

The young man is Caleb, a cowboy who’s come into town looking for some fun. The young woman, Mae, is a pretty girl he flirts with on the street. Before he knows what’s happening, she has taken him through a door he never knew existed into a world he never imagined. A world where the night is so bright it’ll blind you. A whole new kind of experience.

Kathryn Bigelow’s early films are about people walking through that door. Near Dark, Blue Steel and Point Break all deal with characters who find themselves embracing an ecstatic experience of the world, a kind of experience that is equally exhilarating and terrifying. In Near Dark, Caleb’s world is turned inside out when Mae bites him on the neck. Without even understanding what’s happening, he’s soon travelling with a family of vampires who roam the American Southwest, hunting for prey.

Caleb tries to escape, but finds it isn’t easy to get away. He’s horrified by what he sees, but there’s a part of him that’s drawn to these people who “keep odd hours.” Even though they’re a hundred and eighty degrees from the family he lives with back on the farm, there are strong bonds that hold this clan together. Whether hunting, stealing or hiding, they work as a team, and when the chips are down they back each other up. Jesse and Diamondback are the imposing father and mother figures. Severen is the wild older “son” who enjoys toying with his prey. Mae is more passive, and seems troubled by the life she leads. Homer is the angry, lonely boy who has lived more than enough to become a man, but will always be trapped in the body of a child.

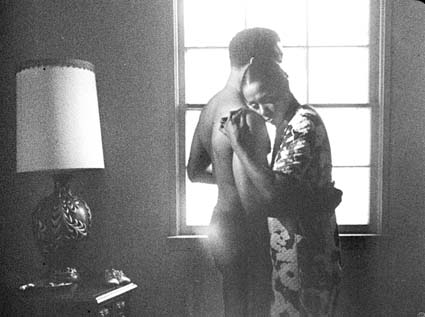

Bigelow and co-screenwriter Eric Red splice two genres together, creating a dark, dynamic fantasy landscape. The western is purely American, and speaks of a clear cut, black and white morality. The horror film hails from the dark corners of Northern Europe, and dares us to step into a terrifying, irrational world. The monsters may die in the final reel, but they live on in our imagination. The tension between these two genres comes across in images that resonate in powerful, inexplicable ways. The shootout at the outlaws’ hideaway becomes a startling, hallucinatory sequence where our hero braves the burning sunlight to stage a daring rescue, and saves his newfound “family”. A barroom confrontation becomes a bloody slaughter, while the jukebox reels out pop tunes in the background. Even a conventional love scene is twisted into something strange and unnerving. Not having tasted blood since his transformation, Caleb is weak and pale. Mae opens a vein in her wrist and offers it to him in order to bring him back to life. He drinks deeply, and feeling miraculously rejuvenated, he kisses her passionately, traces of blood still smeared across his lips.

All this probably sounds like a far cry from the classic westerns of John Ford, but actually Bigelow is a direct descendant of that American master. In fact, among living filmmakers, she is probably the one whose perspective is closest to Ford’s. They are both deeply, unapologetically American, while at the same time obsessively examining the violence and the arrogance that are inextricably woven into this country’s fabric. They’re both poets, relying on a sound, an image, a gesture to express themselves where others would speak to us in words. And they both deal with individuals who find themselves in conflict with their community. The comparison may be easier to see in films like K-19, The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, all of which deal with stubborn outsiders who collide with rigid institutions, but the similarities are very much there in Near Dark. It’s a story about a young man who has to choose between the seductive, dangerous outlaw “family” and returning to the safety and comfort of his own family.

In the end, it’s easy for Caleb to choose because his young sister, Sarah, is in danger. But it’s actually the vampires’ humanity that brings about her release and their own destruction. Mae wrests Sarah from the grasp of her younger “brother” Homer. At a crucial moment, Diamondback urges Caleb and Sarah to run. As the sun rises, Homer chases desperately after Sarah, not as a vampire chasing his prey, but as a child who is losing his only friend. He frantically calls her name as his body is engulfed in flames. Jesse and Diamondback clasp hands, knowing it’s all over, calmly accepting their fate.

Caleb frees Mae of her curse, and the two lovers are united. In Bigelow’s early films, her innocent heroes usually walk away a little wiser and not too much worse for wear. But in her later work she has focussed on characters who are more complex, and the moral issues aren’t so clear cut. From The Weight of Water on, Bigelow’s protagonists aren’t just struggling with their fate, they’re struggling with themselves. There are no more happy endings.

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959)

Many of the earliest American movies were made in New York. While the center of commercial production shifted to Los Angeles in the teens, low-budget producers were still making films on the East Coast during the twenties and thirties. After WWII there was a resurgence of production in New York, and in the fifties independent filmmakers created a style all their own. Instead of Hollywood fantasy, these films embraced gritty reality. Instead of relying solely on studio sets, the directors often shot in the city streets.

Robert Wise was a product of the studio system. Starting out as an editor, he had worked his way up the ladder at RKO and in the forties he became a director. Early films like The Body Snatcher, The Set-Up and The Day the Earth Stood Still had earned him a good deal of attention. At his best, Wise had a taut, straightforward approach that worked especially well in the world of B-movies.

But Odds Against Tomorrow feels totally different from Wise’s studio work. It has a looseness, a freedom that you don’t find in the director’s lean, suspenseful Hollywood thrillers. I think in large part this is because he was working in New York. It may have been the crew, or the locations, or maybe just stepping outside of the Hollywood box, but this movie stands apart from anything he’d done before.

To start with, the tone of Joseph Brun’s photography is different from anything I’ve seen coming out of Hollywood at the time. Brun’s images are rich and complex, but the light is generally diffused, giving us few solid blacks and bright whites, more shades of grey. The film takes place in winter, and the light feels thin and chilly. It’s also interesting to see how much attention is given to things on the periphery, details that don’t advance the story. Working in Hollywood, Wise was known for a direct, no-frills approach. Here the camera lingers on the shadows cast by horses on a merry-go-round, newspapers flying down an empty street, a pool of water rippling in the gutter.

This wouldn’t just be Brun’s doing. I suspect that this willingness to linger on the details is at least in part the work of Dede Allen. Odds Against Tomorrow is one of Allen’s earliest feature credits, but she had been working as an editor for years. Of course, Wise had started his career as an editor, but the rhythms here are definitely a departure from his previous work. My feeling is that this more creative, intuitive approach is probably due to Allen’s involvement. It seems to point toward her later work with Arthur Penn and Sidney Lumet. Instead of moving relentlessly forward, the film allows us to look around and linger on things that don’t advance the plot. The focus is less on the story than it is on mood, atmosphere, character.

The characters are very interesting. Ed Begley is Dave, an ex-cop who got busted and has fallen on hard times. He seems to be a sensitive, caring person, but he’s willing to do some ugly things to get what he wants. Robert Ryan gives a stunning, low-key performance. He has tremendous authority on the screen, and he uses it to pull us inside characters who are deeply flawed and deeply unhappy. Playing Earle, Ryan manages to keep us with him every minute, even though the man is a bitter, violent racist.

Johnny, played by Harry Belafonte, is the most sympathetic of the three, and also the most complicated. At first he appears to be smart, suave and confident, a talented nightclub performer who’s enjoying a certain amount of success. But as we learn more about him, we realize that his life isn’t nearly as sweet as it seems. The failure of his marriage is eating away at him, and his addiction to gambling has put him in a huge financial hole. And race is also an issue for Johnny, though it’s hard to pin his feelings down exactly. When he’s in his own world he seems completely comfortable with his white friends, but when he sees his wife inviting white acquaintances to her apartment, he can’t keep his resentment from boiling over. Belafonte plays the part with a striking mixture of assurance and sensitivity.

We wouldn’t get such vivid performances if the script didn’t provide such interesting characters. The screenplay was written by Abraham Polonsky and Nelson Gidding, based on the novel by William P. McGivern. As with many of the best heist films, the focus isn’t on the job but on the people. The robbery is a mechanism that allows us to observe the lives of these three men, and to watch how they interact. As the pressure builds, we see each of them slowly starting to crack, we see more of who they really are.

And John Lewis’ music provides a rich, resonant background for all of this. The jazz score is another aspect of the film that ties it to the New York school. There were many soundtracks written in Hollywood that incorporated jazz elements, but in New York the filmmakers often turned to actual jazz musicians. Lewis paints a moody, brooding backdrop for this bleak tale of desperation. He’s not afraid to use dissonance, and his brass arrangements make the tension in the story palpable. For the quieter moments he turns to vibes and guitar, which complement the sombre visuals well.

Wise made a number of excellent films in his long career, and he wasn’t afraid to take chances, to try new things. His openness to different approaches is probably one of the reasons Odds Against Tomorrow is such a striking movie. If he had shot it in Hollywood, it might have been a solid thriller. But I think shooting it in New York made it something more.

Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (1927) [Berlin: Symphony of a Great City]

In nineteen twenty seven, Berlin was a city suspended between two wars. Germany had been devastated by the violent conflict which had ended less than a decade before. It was a country still trying to rebuild itself, with mixed success. The capitol was in a dizzying state of flux. The government was fragile, the economy was unstable, but the culture was flourishing. The chaos seemed to inspire artists, writers and composers to break away from the past and imagine a new future.

In nineteen twenty seven, Berlin was a city suspended between two wars. Germany had been devastated by the violent conflict which had ended less than a decade before. It was a country still trying to rebuild itself, with mixed success. The capitol was in a dizzying state of flux. The government was fragile, the economy was unstable, but the culture was flourishing. The chaos seemed to inspire artists, writers and composers to break away from the past and imagine a new future.

Nowhere was this newfound freedom more apparent than in German cinema. Writers, directors and designers explored radical new approaches to making movies, and the films they made attracted a good deal of attention both in Europe and abroad. One of the most original talents to emerge during this period was Walther Ruttman. Ruttman had worked as an artist and an architect before beginning his film career in the early twenties. He began making abstract animated shorts using form and color to create a kind of visual music.

Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt uses images of a vast metropolis to create a different kind of visual music. It is not a documentary, but an attempt to distill the spirit of this great capitol in a cinematic tone poem. Ruttman didn’t want to tell a story. He wanted to compose music with images. In this film he creates a visual symphony that incorporates the frenzied energy, the languorous calm, the lights, the shadows, the madness, the excitement of a great city.

In the same way that a symphony is divided into movements, the film is divided into five parts, or “acts”. We observe the life of the capitol through the course of a day, starting at dawn and ending at midnight, with each of the five parts focussing on different aspects of this sprawling urban giant. And just as a piece of music has various themes that recur throughout, there are visual motifs that are used repeatedly, binding the torrent of images together.

The opening sequence is a perfect example of the film’s musical structure. Ruttman begins with images of water, rippling gently. This segues to an animated sequence, where horizontal lines are crossed by diagonal lines falling against each other in a rhythm that builds slowly. And then we’re at a railroad crossing as barriers fall into place across the tracks. Suddenly a train is hurtling across the screen, and soon we’re experiencing the motion of the train as it rushes through space, trees flashing by so quickly they become abstract shadows flying past in a blur. After tearing through the countryside, speeding past the slums on the outskirts, the train gradually slows, the rhythm gradually slows, as we enter the city.

From this powerful opening, the film goes on to show us a panorama of life in Berlin during the twenties. We see children stroll through the streets on their way to school and workers march through the gates at massive factories. We see the wealthy consuming their banquets with relish and the poor begging for scraps on the street. Machines play a central role in the film, spinning, stamping, steaming, smoking. At times the action is fast-paced and frenetic, pulling us into the aggressive rhythm of the city. But the director also shows us that there are quiet moments, spaces for relaxation and leisure.

Throughout the film Ruttman focusses on the crowd rather than on individuals. He seems to be standing back, trying to act as a neutral observer, but at times he does comment on the images. Scenes of crowds milling through the streets on their way to work are juxtaposed with a herd of cattle making their way down a road. A frenzied montage of men in the business world is matched with footage of dogs fighting. And there are moments when Ruttman pushes the film into abstraction. Typewriter keys melt into a geometric swirl of letters. Pinwheels fill the screen, spinning relentlessly. Words come rising rhythmically off pages of newsprint.

The images are half of the film. The other half is the score. Sadly, the music originally written for Berlin by Edmund Meisel has apparently been lost. But the version of the film that I’ve seen, which was released by Kino Video in the nineties, has a newly composed score by Timothy Brock which is beautifully suited to Ruttman’s cinematic tour de force. With a movie like this, the composer isn’t just writing individual cues as needed. Brock’s score for Berlin is a complete work. He must have spent a lot of time with the film, getting to know it intimately before he started, because his music is perfectly matched to the images on the screen. The driving motion of machines is accompanied by a furious string section playing overlapping rhythmic figures. A lull in the early afternoon is scored with lyrical winds and reeds. And to underline the frightening intensity of this massive city, the composer rolls out thundering percussion as needed. Brock’s score gives this film everything it needs. He nails it.

Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt is a thrilling, visionary film. I’m so blown away by what Ruttman accomplished that I’d like to hold him up as a hero. But I can’t. As I said earlier, at the time this film was made, Germany was between two wars. The country’s faltering economy finally collapsed, driving a desperate nation to desperate solutions. By the early thirties the German people were embracing Adolph Hitler as their leader. While many German filmmakers fled the madness, Ruttman stayed behind and worked for the Nazis, making propaganda films. In nineteen forty one he was injured while filming at the Russian front, and died shortly after.

It’s baffling to see an artist with so much talent and so much imagination embrace the horror of Nazism. How could someone so intelligent embrace a philosophy that worshipped violence and death? As I’ve grown older, I’ve become more and more aware of the disturbing fact that there are people who have tremendous gifts who also do truly monstrous things. I don’t understand it. I don’t think I ever will.

But just as I can’t embrace Ruttman as a hero, I can’t dismiss his work. Berlin is an exhilarating panorama of a modern metropolis in all its terrifying wonder. A silent film that uses the power of images to reach across time and space to show us a place, a people, that have long since vanished. And also a work of art that, if we look closely, might remind us of who we really are.

In the Cut (2003)

There’s some disagreement about whether In the Cut is a thriller or not. It was certainly marketed that way, and I feel pretty certain that’s the way the filmmakers pitched the project. Jane Campion had enjoyed critical and commercial success with The Piano, but her next two films got mixed reviews and did poorly at the box office. My guess is that she decided to play it safe and make a genre film about a serial killer in order to improve her track record in Hollywood. The funny thing is, Campion doesn’t know how to play it safe. She’s always pushing the limits, and with In the Cut she pushed them way beyond what critics and audiences were willing to accept. She may have set out to make a thriller, but instead she made a darkly sensuous, deeply disturbing movie that’s about as far from the standard Hollywood murder mystery as you can get.

Anyone who watches this movie expecting a thriller is going to be totally disappointed. In the Cut isn’t just another movie about a serial killer stalking women. In fact, Campion isn’t even interested in the mechanics of making a suspense flick. Rather than giving us a routine genre film where the women are basically just bait, she broadens the concept to include the everyday violence that men commit against women, whether it’s verbal, emotional or physical.

The main characters are half-sisters, Frannie and Pauline, played by Meg Ryan and Jennifer Jason Leigh. They had the same father but different mothers, and this is the psychic crux of the whole movie. Their father married four times, apparently going from one woman to another, and both daughters are still dealing with the damage, still carrying the hurt of having been abandoned. Throughout the film we see scenes of a fantasy courtship, Frannie’s mother and father meeting and getting engaged as they ice skate in a wintry landscape. The images have a fairy tale feel, but that doesn’t mean there will be a happy ending. In fact, by the end of the movie we see that this story is as brutal as anything set down by the Brothers Grimm.

Actually, the whole film is a fairy tale. Symbols abound, and Campion isn’t shy about the way she uses them. New York City becomes a whirling surrealist landscape filled with floating petals, flowery hearts, jeweled rings and tall red lighthouses. As in a fairy tale, the half-sisters are complete opposites. Frannie is a repressed college teacher who lives in a world of words. She isn’t afraid of men, but she is determined to keep them at arm’s length. Her sister Pauline is completely uninhibited and embraces the sensual side of life, going from one man to another looking for love.

In the Cut isn’t pornographic, and it’s not erotic either. Campion finds a space between the two, and it’s an uncomfortable space. The sex is unusually explicit for a Hollywood movie, but it doesn’t exploit sex the way many commercial films do. At the same time, the scenes that show Frannie and Molloy making love aren’t really a turn on. There’s a current of tension that runs through every scene, and the threat of violence always seems to be lurking just beneath the surface. This isn’t just because the film is about a serial killer. Bloodshed and death seem to find their way into even the most casual conversations. The film starts with the sisters talking about how slang words are either about sex or violence or both. The macho banter of the two cops reduces women to nothing more than a hole. Frannie meets with one of her students and he talks obsessively about John Wayne Gacy.

Campion creates this dark, disturbing world with the help of some gifted collaborators. Production designer David Brisbin and art director David Stein give us an expressionist New York defined by dirty reds and fetid greens. Cinematographer Dino Beebe takes this palette and uses it to help define the film’s murky, ambiguous mindscape. And the images are complemented beautifully by Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson’s abstract, brooding score. Technically, yes, the film is a mystery, because it’s about the search for a killer. But on a deeper level, it’s truly mysterious. Campion isn’t afraid to show us a world where conflicting emotions lead people into random, impossible relationships and feelings that can’t be resolved. She isn’t telling us to embrace sex or to try and escape violence. She seems to be saying that both are part of life. And that we should get used to it.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010)

Scott Pilgrim satirizes its subject at the same time that it’s giving it a big warm hug. The characters all live in a swirling pop culture universe where ordinary physical laws don’t apply. Characters move through three or four different settings in the course of the same conversation. Written words fly across the screen. Doors appear out of nowhere. And Wright pays as much attention to sound as he does images. He underscores the action by weaving together an intricate collage of ethereal voices, grating static and video game chimes. Most of it slides by without our being “consciously” aware of it, but Wright knows that it’s still having an impact. He understands how important sound is to the rhythm and the texture of a film.

When we first meet Scott, he’s an arrogant little jerk. Totally self-absorbed, he expects the world to revolve around him, and seems baffled when it doesn’t. Completely insecure, the smallest slight sends him into depression. But he meets a girl he really cares about, and she makes him raise his game. He realizes that if he’s going to be with her, he has to fight for her. It’s a standard coming of age story, but Wright tells it with a light touch and a wicked sense of humor. It may not be deep or heavy, but it is heartfelt.

Once more, we find Michael Cera playing a clueless nerd, and once more, he somehow makes the character interesting and engaging. He is truly obnoxious during the first part of the movie, but as he slowly, painfully starts learning what it means to take responsibility for his life, he starts to earn your respect. It helps that Cera has an amazing supporting cast to back him up. And Wright again deserves credit for the way he handles the actors. All the performances are stylized to fit the movie’s tone, but they’re not flattened out, as is so often the case when people try to make comic strip movies. All the characters are bursting with energy, and it’s hard to single anybody out because they’re all so enjoyable to watch. Kieran Culkin is razor sharp as Scott’s gay roommate Wallace. Ellen Wong somehow manages to make a character named Knives believable, first as an absurdly innocent schoolgirl, and then as Scott’s insanely jealous ex-girlfriend. As Gideon, Ramona’s rock producer ex-boyfriend, Jason Schwartzman is so unctuously hip that you want to punch him. He’s great. And while everyone else is freaking out or falling apart, Mary Elizabeth Winstead brings a low-key vibe to the part of Ramona, sort of like the calm at the center of the storm. She has a matter-of-fact openness that stands in stark contrast to Scott’s raging insecurity. You can see why he’s drawn to her, and also why she’s such a huge challenge for him.

Scott Pilgrim tanked at the box office. According to the IMDB it only earned thirty million in its US release, but most of the people I know who saw the movie loved it. I wouldn’t be surprised if in five years or so it’s considered a cult classic. It’s probably not for everybody, and no doubt plays better with younger viewers. But it is a legitimately awesome flick. It seems like most of the comedies that get released these days are competing to gross us out. What a welcome surprise to see a smart, stylish comedy that relies on wit and imagination.

If only we could clone Edgar Wright.

Preserving the Future

Last week I came across a post on David Bordwell’s site which gives an in-depth look at some of the challenges we’re facing in terms of preserving both film and digital. It’s long, but it’s well worth reading. I was especially interested in the essay by Margaret Bodde, Executive Director of the Film Foundation, regarding preservation of digital media. As the studios rush to embrace digital, they seem blithely unaware of the fact that preserving media in this format is much more complicated, much more work intensive, and much more expensive than preserving film.

Anyway, if you’re into this stuff, I think you’ll find it pretty interesting. The link is below.

The Crimson Kimono (1959)

Nowhere are Fuller’s strengths and weaknesses more evident than in The Crimson Kimono. The film’s main characters are two LAPD detectives, Joe, a Japanese-American and Charles, an Anglo. From a twenty-first century perspective, it may be hard to understand how provocative this was in the fifties. The Crimson Kimono was released less than fifteen years years after WWII, when Japanese-Americans had been rounded up and sent to prison camps, ostensibly because the US government felt they might be a threat to national security. For most filmmakers of the time, it would have been daring enough to introduce a Nisei cop in a crime thriller. But the central conflict in the story actually comes out of the fact that Joe gets involved in a relationship with a white woman. How this film got released by a major studio back in nineteen fifty nine is beyond me.

The turning point for Joe is when he falls in love with Chris. She loves him as well, but he suddenly becomes aware for the first time that as a Japanese man he is seen as an outsider. In reality this is completely absurd. It’s hard enough to believe that any Japanese-American could come of age in mid-century America without having encountered racism, but the idea that Joe would fit right in with the LAPD at that time is laughable. Still, Fuller deserves credit for even talking about this kind of alienation in the fifties. Whether or not we accept the specifics of Joe’s story, the director was trying to make the point that in this “land of opportunity”, there were many people who felt excluded.

Fuller opens the film, as he often did, with a wallop. The opening shots bring us to a burlesque theatre in downtown LA. We see Sugar Torch dancing onstage as the band in the pit belts out a raucous tune. Moments later she’s lying dead on the crowded street outside. Much of the film was shot on location, and we get a good look at Los Angeles in the fifties. But even more important, the film is an amazing document of the Japanese-American community during that era.

Fuller’s camera follows the detectives as they roam through the streets of Little Tokyo. We see Japanese women working in a wig shop. Cooks in a kitchen making rice cakes. A couple of nuns standing in front of the Maryknoll School. To my mind the most remarkable scene shows Joe looking for an older Japanese man who may have information about a witness. He finds Mr. Yoshinaga at the Evergreen Cemetery, where the man is visiting the grave of his son, killed in WWII. Few Americans were aware then (and fewer now) that Japanese-Americans fought with the Allies in Europe. To make sure no one misses the point, Fuller lingers over monuments dedicated to these men. Joe asks Mr. Yoshinaga for help, and the man agrees, but says he must first attend a memorial service for his son. We follow him into a Buddhist temple to witness the ceremony, watching as the priest strikes a gong, taps a wood block, recites a prayer. This scene does nothing to advance the plot, but it opens a window on a world that most Americans have never seen. A world that’s right in our own backyard.

Whatever his faults as a filmmaker, Fuller challenged himself and he challenged his audience. It’s not just that he didn’t support the status quo. He was infuriated by the complacency with which most Americans accepted the bland reassurance that Hollywood dished out during the studio era (and still dishes out today). He tried to show us America in all its diversity, all its contrasts, all its complexity.

Really, he was trying to get us to take a long, hard look at ourselves.

Time Out

With the holiday season in full swing, I’m going to be taking some time off. I won’t be posting again until around the middle of January. Hope all of you have a safe and happy new year.

And whether or not you celebrate Christmas, remember it’s better to give than to receive. Keeping that thought in mind, I hope you’ll take a minute to visit the National Film Preservation Foundation web site. In recent years the NFPF has been involved in many worthwhile restoration projects, including a John Ford comedy thought to be lost, an early Fleischer Bros. cartoon and portions of a silent film that Alfred Hitchcock worked on. If you’d like to support their work, or even if you’d just like to learn more, click on the link below.

Killer of Sheep (1977)

Often a filmmaker’s most original work is the work he does outside the system. The constraints that directors have to deal with in making a commercial feature can tie them in knots. Producers who invest large sums of money in a project generally want something safe because they feel that’s the best way to turn a profit, which is why so many of the films we see have a ring of familiarity. A director may set out to make a movie that’s completely unconventional, but by time they’ve finished negotiating with the money men their groundbreaking work of art often becomes a rehash of last year’s hit.

Charles Burnett made Killer of Sheep when he was a student at UCLA in the seventies. It has the fearless originality, the breathtaking openness, the disturbing directness that maybe only a young artist is capable of. Working on a shoestring, using unknowns as actors, assisted by a crew you could probably fit in a VW, Burnett just made the film he wanted to. It’s a deeply personal and wrenchingly honest look at life in Watts, a run down, low income suburb of Los Angeles.

The film starts with a brief prologue where a teenage boy is first scolded by his father and then slapped by his mother for not taking his brother’s side in a fight. Early on the message is being drilled in. Violence is a part of life. Get used to it. We can choose not to fight, but we can’t escape the fight. It’s all around us. And the world is always trying to drag us into the fray.

Violence pervades the slowly decaying neighborhood where Stan lives in a small house with his wife and two children. Caught in the act of stealing a TV, a petty thief flies into a fit of rage when one of the neighbors calls the police. A couple of thugs come calling, looking for someone to help them out with a murder. And Stan works in a slaughterhouse, butchering sheep in order to make a living.

The scenes of Stan doing his job are brutally graphic. Sheep are kept in pens until they’re hung up and killed. Their carcasses are carried down a line as they’re skinned and dismembered. Stan is a gentle soul, but he spends his days slaughtering animals and we can see that it’s grinding him down. Trapped in a life he can’t escape, he seems exhausted and dazed. He talks about how he can’t sleep at night. His wife wants him to make love to her, but he rebuffs her. He barely speaks to his children.

Stan may literally be a killer of sheep, but everybody who lives in this depressed neighborhood is caught in a pen, waiting to be slaughtered. Burnett spends a good deal of time showing us the local children at play. They’re just kids, and they play the same games that kids play everywhere, but their aimless, innocent fun often seems to involve fighting, wrestling, rocks and BB guns. Violence bleeds into their lives early on.

This all may sound pretty bleak, but Burnett is so passionately engaged with his characters and the lives they lead that his film has a kind of subdued radiance. Wound up with the suffering and the sadness of Stan’s world is an implacable love that somehow survives. The glorious, eclectic score plays a major part in putting this across. Burnett brings together a variety of artists working in a range of styles, from Paul Robeson to Elmore James, from Scott Joplin to William Grant Still. But it’s Dinah Washington singing This Bitter Earth that reveals the film’s core of love wrapped up in pain. Near the end of the movie Stan and his family return home after a flat tire ruins their outing. It’s been a frustrating day, but as he’s sitting on the sofa with his wife he suddenly seems able to show her some tenderness. The final scene shows him back in the slaughterhouse, doing his job, but for the moment he seems to have found a reason to keep moving forward. And the last thing we hear before the credits is Washington singing the line, “…This bitter earth may not be so bitter after all.”

Does Anybody Still Shoot on Film?

Yeah, I know digital is still the standard. I have no illusions about a revival of film. But it’s good to know that filmmakers still have a choice.