To Catch a Thief (1955)

I’ve seen To Catch a Thief a number of times. At first I dismissed it as fluff, but I have to say it’s grown on me over the years. Even if it’s not up there with Hitchcock’s best, it’s still a pretty interesting piece of work. It was released in the mid-fifties, halfway through a decade in which the director made a remarkable series of movies, including Strangers on a Train, Rear Window, Vertigo and North by Northwest. During this period Hitchcock created some of his most complex, challenging films, and amazingly, he also enjoyed a long winning streak at the box office.

Like other directors who succeeded in Hollywood, Hitchcock understood that he was only able to hold on to his artistic freedom as long as he was able to produce money-making films. It was a balancing act. Sometimes he took chances, and his more daring projects didn’t always fare well at the box office. So he also made films that were calculated to please audiences, films that were conceived primarily as entertainment.

Which doesn’t mean to say that To Catch a Thief is completely superficial. One of the things that makes Hitchcock’s work so interesting is that he could deliver a film for the mass audience that was still subversive. Here he gives us the beautiful stars, the sumptuous sets and the stunning location work on the French Riviera, but at the same time he manages to pose some questions about the glamorous lifestyle that were seeing on the screen. He’s feeding us a slice of cake, but he also makes a point of asking if this is what we should be craving.

On the surface, the film’s tone is light and breezy, and John Michael Hayes’ script has a sharp wit that keeps us from taking it too seriously. The director is offering his audience a voyeuristic thrill by setting the film on the beautiful and luxurious French Riviera. Cary Grant plays John Robie, a gentleman jewel thief who’s gone straight. Grace Kelly plays Frances Stevens, a spoiled rich girl vactioning with her mother. Everything you need for a light, sophisticated thriller.

When I first watched To Catch a Thief, all I saw was the glittering surface. But on subsequent viewings, I started to catch interesting undercurrents. While Robie is a professional thief, the film makes the point that we’re all thieves in one way or another. Hughson, the straightlaced insurance agent who’s trying to recover the stolen jewels, gets uncomfortable when Robie calls him out on the fact that he’s padding his expense account. Hughson doesn’t like it either when one of his clients points out that selling insurance is basically gambling. And Frances, the headstrong heiress, wants to join Robie as a partner in crime, planning a robbery as though it was an amusing game. Throughout his career, Hitchcock kept reminding us that the line between law-abiding citizen and desperate criminal is very thin. The unfortunate heroine in Blackmail, the smug athlete in Strangers on a Train, the glib ad man in North by Northwest, all feel comfortably snug in their daily lives, until a twist of fate puts them on the wrong side of the law. The films may be fiction, but how many of us can say there hasn’t been a point in our lives when we could’ve crossed that line ourselves.

It’s redundant to call attention to Cary Grant’s striking skill and suave assurance. He’s pretty much perfect as the reformed thief. And I don’t want to spend a lot of time talking about Grace Kelly’s deft blend of cool wit and casual confidence. I’d rather focus on the supporting cast, which is just as impressive as the leading actors. John Williams made a career out of playing proper Brits, but here he gets a chance to have fun with the role. His drily understated performance is a joy to watch. Brigitte Auber has a strong and lively presence as Danielle, the amoral girl who wants to lure Grant back to a life of crime. But my favorite is Jessie Royce Landis as Frances’ down to earth mother. Landis was often cast as a matron, but in her films with Hitchcock she got to show how much she could bring to those roles. She does what the best character actors knew how to do, and that is to take a type and turn it into into an individual. In this film she gives one of the most enjoyable performances I’ve ever seen on the screen.

In making To Catch a Thief, Hitchcock was surrounded by an amazing team of collaborators. The film’s bright, crisp visual style was crafted by cinematographer Robert Burks working with art directors Hal Pereira and J. McMillan Johnson. Edith Head’s costumes add a layer of sumptuous style. George Tomasini worked as an editor on a number of Hitchcock films, all displaying a sharp sense of pace and rhythm. The only one of the director’s major collaborators from the fifties that’s missing is composer Bernard Herrman, but Lyn Murray’s score is enjoyable and energetic.

The Hollywood system has always demanded that filmmakers bring in the bucks. Hitchcock knew he had to balance his more personal projects with mainstream entertainment. But he also knew that these more conventional films could hold unconventional ideas. To Catch a Thief may appear to be nothing more than a slick, mainstream movie, but underneath the smooth, seductive surface, you’ll find that Hitchcock’s cold, hard intelligence is still at work.

Shadows (1959)

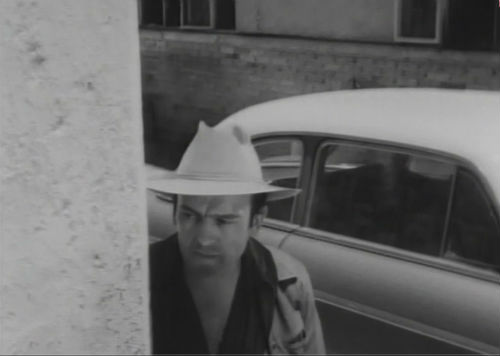

An intense young man walks the streets of New York while a moody, abstract bass line murmurs to us in the background. A young woman stops under a bright theatre marquee to check out the lurid display as a rambling solo sax underscores the scene’s sexual tension. In John Cassavetes’ Shadows, the jazz soundtrack doesn’t just complement the visuals, it’s an integral part of the director’s approach. The spontaneity and sensitivity of the music reflects the loose, open-ended feel of the movie. It’s not just a different style. It’s a different way of thinking about film.

The credits tell us that Shadows was improvised, which isn’t really true. It did grow out of improvisations by the actors, and Cassavetes was open to their inspiration during the shooting. But even if there wasn’t a traditional script, the director had definite ideas about the film’s shape and structure. Cassavetes knew where he wanted to go, even if he didn’t always know how to get there. It was his first film, and he has acknowledged that it’s uneven. Shadows may be messy and chaotic, but its loose, freewheeling approach allows the actors to connect with us in ways they never could in a more conventional film.

Just as a jazz musician takes a melody and makes it their own by opening themselves up to the moment, Cassavetes and his collaborators start with a basic structure and allow themselves the freedom to be spontaneous. They’re not locked into the demands of a commercial film, where the story is crucial and everything is planned and prepared. They take chances, they make mistakes. Sometimes this approach doesn’t work, and the film just seems amateurish and ragged. But at other times it gives us moments that seem remarkably true. An uncomfortable silence that says more than any words could. An awkward gesture that reveals a character’s insecurity. These sparks struck by accident illuminate the film. They give it an immediacy we don’t often see on the screen.

Shadows has been praised for its originality, and in some ways it did blaze new trails. But Cassavetes had his influences, and to a degree the film was an outgrowth of trends that had begun to develop in the late forties. After WWII, many filmmakers had started to venture away from soundstages and shoot their movies on real locations. Europeans, especially the Italian Neo-Realists, had forged a new kind of filmmaking that was rooted in everyday life. And in New York in the fifties there was a growing movement to create an independent cinema. Morris Engel, Shirley Clarke and Lionel Rogosin had all made low-budget films using actual locations.

The film centers on three siblings living together in New York. The three are played by Hugh Hurd, Ben Carruthers and Lelia Goldoni, and the actors’ first names are adopted by the characters in the film. Hugh is the oldest, a singer who’s having trouble getting gigs. Ben, in the middle, plays trumpet, though he’s more interested in partying than making music. And Lelia, the youngest, seems to just be trying to find herself. Shadows doesn’t have a central story. Or rather, it tells a few different stories, and they overlap in interesting ways. The characters hang out in bars, go to parties, make love and have fights just like real people do. The film doesn’t build to a conventional climax. There’s no tidy resolution at the end. Hugh, Ben and Lelia just go on with their lives.

The music in Shadows is by Charles Mingus and Shafi Hadi, but apparently recording the soundtrack was just as chaotic as the rest of the production. From what I’ve read, Cassavetes wanted Mingus to compose the score, but apparently the two had a series of disagreements, which may have had to do with money or deadlines or both. No two accounts I’ve read agree on the details, but little of Mingus’ music ended up in the final film. Apparently Cassavetes worked with Hadi on recording the sax solos that make up most of the score. However difficult the process was, the end result gives the movie a tone that is absolutely unique. The cues are discrete pieces, reflecting the mood of the individual scenes. And the freedom we hear in the music is completely in tune with the spirit of the movie. It doesn’t tell us what to feel. It allows us to feel.

Summer Vacation

I’ve been having too much fun to think about posting lately, so I’m taking the rest of July off. I’ll be back in August. Hope you’re enjoying your summer as much as I’m enjoying mine.

Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001)

I was a teenager through most of the seventies, and I spent a fair amount of time in Santa Monica, but I had no idea that a revolution was going on there. While I was catching as many local bands as I could, and camping out at revival theatres that showed stuff by Welles and Godard, there was a whole other scene happening that eventually would change the world. I missed it completely. I’d never even ridden a skateboard.

Dogtown and Z-Boys doesn’t just document a sport. It captures a cultural shift. Using footage from the seventies along with an explosive collage of music from the time, the film shows how a rowdy band of kids living in an urban wasteland ended up becoming heroes to a generation. Skateboarding became a vehicle that would carry art, style and attitude to kids all over the world. Dogtown and Z-Boys is an exhilarating look back at how it all happened.

This movie has incredible energy. While it uses the standard talking head format for the interviews that tell the movement’s story, the footage from the past gives us a swirling, kaleidoscopic view of the seventies. If you’ve seen video of skateboarders doing their stuff, you know movement is everything, and I’m not just talking about the kids riding the boards. The camera leaps, jerks, swoops, trying to capture whatever’s happening. The images careen across the screen, sometimes flashing past so quickly it’s hard to say exactly what we’ve seen. The filmmakers splice it all together in inventive and expressive ways, capturing the energy of a movement that was all about movement. They also do an excellent job of using the present day interviews to provide context without slowing the film down or turning it into a lecture.

The film begins by giving us a sketch of the surfing scene in Santa Monica, Venice and Ocean Park back in the early seventies. The area had gone from oceanside suburb to urban wasteland in the space of about a decade. The guys riding the waves in that part of town had an aggressive style and were openly hostile to outsiders. Jeff Ho, Skip Engblom and Craig Stecyk opened up a surf shop where young surfers would gather to work and hang out. But somewhere along the way these kids turned from surfing to skateboarding, and the rowdy, crazy energy they’d shown riding the waves got channeled into their moves on concrete. Ho, Engblom and Stecyk acted as godfathers and midwives to the movement, creating the Zephyr Team, which was the tightly bound and tightly wound unit that was soon shaking up the skateboarding world.

While the film may appear chaotic, it’s actually very carefully constructed to give us not just the stories of the individuals or the history of the team, but also to give us the necessary context to understand what was actually going down. The film deftly weaves together observations about society, technology, commerce and culture to give us a well-rounded picture of the time and the place these kids grew up in, and to explain why their brash style connected with teens all across the country.

The one gripe I have with Dogtown and Z-Boys is that the makers don’t fully acknowledge their involvement in creating the story they’re telling. Sure, if you look at the credits you’ll see that it was written and directed by Craig Stecyk and Stacy Peralta. And in watching the movie you’ll make the connection that Stecyk’s work for Skateboard magazine garnered a lot of attention for the Z-Boys, while Peralta was one of the sport’s first stars. These two played a huge role not just in creating the initial scene, but in publicizing it and shaping the perception of it. I’m not bothered by the fact that they’re writing and directing the movie. Certainly they’re well qualified to tell the story, and as a piece of filmmaking Dogtown and Z-Boys is outstanding. But if you set out to make skateboarding a phenomenon, and then you make a documentary that shows how skateboarding became a phenomenon, you really have to acknowledge your dual role as subject and storyteller. Not just by putting your name on the credits, but by allowing that to be part of the fabric of the film. While I don’t distrust Peralta and Stecyk, I don’t think they’re being completely honest. In other words, I have no problem with them giving me a subjective account of what went down. I just want them to acknowledge that it is a subjective account.

Aside from that, I totally love this movie. These guys are smart and funny, and they have some great stories to tell. The footage from the seventies takes me back to the days when LA seemed like a vast, decaying paradise that you could wander through forever. And the score, featuring Jimi Hendrix, Alice Cooper, Pretenders and many others, matches the searing energy of the images.

Dogtown and Z-Boys is a joy to watch.

After Hours (1985)

There is a scene in After Hours where the main character, Paul, is asking a bouncer whether he can enter a club, and the bouncer responds by paraphrasing Kafka. This might seem like just an academic in-joke, but actually I think it has a lot to do with the spirit of the film. Joseph K., the central figure in Kafka’s novel The Trial, is a mid-level bureaucrat who finds his life slowly being consumed by a vast bureaucracy he can’t begin to understand. Paul, the central figure in After Hours, is an office worker who goes out one night to meet a girl and finds himself caught up in a web of events that threaten his sanity and his life. Both characters start as young, smug, middle-class men. Both run into situations that overwhelm them, eventually turning their world upside down. Both end up realizing how little control they really have over their own lives.

Joseph Minion’s script for After Hours starts by showing us Paul in his office, training a co-worker, completely bored with his situation and disengaged from the people around him. Later we see him alone in his apartment, impatiently flipping through the channels on his TV, looking for something that will hold his interest. Finally he goes out to have a cup of coffee and read a book. (The book is Tropic of Cancer, and to my mind the fact that Minion references both Henry Miller and Franz Kafka in the same movie says a lot about the conflicts the author is dealing with.) Unexpectedly, a young woman, Marcy, starts speaking to him. Paul is immediately interested, and she ends up inviting him to the loft she’s staying at. But what he thought would be a simple rendevous turns into an extremely uncomfortable, emotionally charged situation. Paul tries to back out, but it’s too late. From that point on, everywhere he turns there’s a new challenge, and it seems there’s no way he can win. Minion draws us into situations that at first seem completely realistic, then slowly become incredibly bizarre. But the development is so carefully structured that we’re with the film all the way.

Minion’s script meshes beautifully with director Martin Scorsese’s vision. At the time he got involved with After Hours, Scorsese had seen another project fall through and he was anxious to get started on something else. He was given the script and it impressed him. He may have recognized something of himself in Minion’s work. The story has elements that are familiar from the director’s other films. Like many other Scorsese heroes, Paul’s finds that the pursuit of sex can be dangerous, even life-threatening. He meets an attractive woman, and all he wants to do is go to bed with her. But the kind of encounter he’s looking for, the easy comfort of holding his body against someone else’s, keeps eluding him. In Scorsese’s world, the flesh is inherently corrupt. There is no such thing as simple sex. Paul goes to the woman’s loft hoping to hang out for a while and then slide into her bed. But in the course of talking to her, he finds out that she has some major issues. What’s more, she may be a burn victim. Paul is attracted to her physically, but he’s freaked out by what he might discover if she takes off her clothes. And the crazy thing is, he still wants to know.

For Scorsese and Minion, the body is a seductive, fragile, creepy threat. Marcy’s roommate is a wiry New York artist who makes sculptures of human forms writhing in agony. In a restroom, Paul glances at the wall and sees a drawing of a frightening castration scenario. Hiding on a fire escape, he watches as a woman shoots her husband. Symbols of sex, violence and death permeate the film. There is no safe haven. Even places and people that might at first seem benign slowly morph into ugly encounters. A friendly waitress becomes a clinging psycho. An ice cream truck roams the neighborhood carrying angry vigilantes.

The beautiful and scary nighttime landscape that Paul finds himself lost in is photographed by the amazing Michael Ballhaus. The film was shot on a really low budget, and Scorsese needed somebody who could work fast. Fortunately he connected with this talented German cinematographer, who gave the film an eerie, haunting beauty. Ballhaus’ work appears to be simple and straightforward, but he has an amazing knack for capturing subtleties of light and color. He was the perfect choice for After Hours. Howard Shore’s sinister score complements the look of the film nicely. The music is fairly minimal, and that was the right approach to take. The subtle synth tones that accompany Paul’s manic journey through the dark Manhattan streets are an effective counterpoint to his increasingly frazzled state of mind.

As the light of dawn creeps over the city, Paul, tired, exhausted, tattered, is dumped out of a van in front of the office building he works in. He slowly picks himself up off the street. The massive front gates swing open magically. And Paul, rather than questioning the situation, rather than cursing his fate, walks quietly inside. He takes the elevator up to his floor, walks across the empty office, and sits down at his desk.

He’s stopped struggling. He’s learned acceptance.

Nashville (1975)

I would guess I was thirteen or fourteen when I first saw M*A*S*H. I loved it, but it also kind of freaked me out. I had never seen anything like it before, and it was unsettling in a way I couldn’t explain at the time. Part of it was certainly the black humor and the rampant sex, but also it just felt different. It wasn’t like a Hollywood movie. The director had broken a lot of the rules that commercial films were supposed to follow, giving M*A*S*H a rhythm and a vibe that was startling and liberating. A lot of that had to do with the sound.

Robert Altman was thinking about sound in a way that nobody else was at the time. He had a brash, iconoclastic approach to filmmaking that not only asked audiences to change the way they looked at movies but also the way they listened to movies. Up til nineteen seventy, the vast majority of American filmmakers mostly thought about sound as a matter of recording dialogue. If you could hear the actors clearly and understand what they were saying, that was good sound. Altman trashed that approach. He spent the early seventies trying out different ideas, looking for ways to make his work as rich aurally as it was visually.

Nashville is one of the early peaks in Altman’s career. Aside from all its other virtues, it has a soundtrack that is incredibly dense and dynamic. Layers of dialogue are mixed with background noise and source music to create a sprawling aural landscape. You won’t catch every line of dialogue, and you don’t need to. The movie doesn’t single out the stars, doesn’t tell you what you should be paying attention to. There are multiple stories that criss-cross and overlap, sometimes tin a single scene. You get to decide what you want to focus on.

One of Altman’s key innovations was to get away from the standard boom mike, which records dialogue and background noise together. He started using multiple mikes attached to the performers. This way each actor was recorded on a separate track, which could then be mixed in any way the director wished. This process was way more complicated than the traditional approach, and Altman was lucky to have a number of skilled people working with him. Jim Webb and Chris McLaughlin handled the multi-track recording. William A. Sawyer served as the sound editor and Richard Portman was the re-recording mixer. I don’t know of anyone before Altman who even came near to creating this kind of complex aural environment. He gives us layers, he gives us textures. When you watch the movie, don’t just focus on the dialogue. Listen to the sound.

The script, by Joan Tewkesbury, was written with this approach in mind. Nashville was conceived as a panorama of America, a tapestry with multiple stories woven together. Tewkesbury and Altman discussed the basic structure, talked about specific characters, and she spent some time getting to know the city. Though the film has a loose, spontaneous feel, Tewkesbury has said that for the most part Altman stuck to the screenplay. But some actors did offer their own ideas about the characters they played, and in some cases these were incorporated into the film.

One of the most important instances of this is the scene where Barbara Jean, the frail country music star who’s just gotten out of the hospital, is performing in a crowded amphitheatre. According to Patrick McGilligan, Tewkesbury initially had the character fainting in front of the crowd. But the actress, Ronee Blakley, felt she needed to take the character farther and came up with a meandering, stream-of-consciousness monologue which makes it clear that Barbara Jean can barely keep it together. Altman, after first telling her to stick to the script, allowed the actress to go and ahead and play the scene her way. It’s one of the most powerful moments in the movie.

This character, the country music star whose life is falling apart, is central to Nashville. You might even say she gives the movie its soul. Barbara Jean is both radiant and ethereal. Overflowing with warmth and kindness when she’s with her fans, but bitterly unhappy when she’s alone with her husband/manager. She’s going to pieces, and doesn’t seem to be able to pull herself together, but when she’s onstage singing she soars. In her music, in her voice, she’s the embodiment of the humble simplicity that’s at the center of country music mythology.

That mythology isn’t just central to Nashville’s image of itself, it’s central to America’s image of itself. The film was released just before the nation’s bicentennial, and it’s clear that Altman is using the country music capitol to offer his vision of America. The ideal of the simple, hardworking men and women who do their jobs and care for their families without raising their voices to complain is one that country songwriters have returned to over and over again. And politicians have taken up the refrain in countless campaigns, singing the praises of the God-fearing folks who live in the heartland, the great “silent majority” that keeps the country going through thick and thin.

Altman skewers that myth over and over again in Nashville. But he doesn’t discard it. In fact, though Altman spends a lot of time tearing away the lies and the hypocrisy, it’s because he wants to find the truth at the heart of that myth. The director does spend a good deal of time holding his characters up to ridicule, but he lets us know that they have other sides, too. There are moments in Nashville where these people surprise us, where they turn out to be better than we thought they were.

One character who surprises us is Haven Hamilton, and in large part this is because Henry Gibson plays the part with such smooth cunning. As obnoxious as Hamilton is at times, the actor keeps him from becoming overbearing. He strikes a careful balance between arrogance and innocence. Gibson is a wonderfully gifted actor, but Altman is one of the few filmmakers who knew how to use him. The director gets remarkable performances from many of the cast members. I mentioned Ronee Blakley above, and she is phenomenal as Barbara Jean. It’s to her credit that she immersed herself in the character so thoroughly that she was able to build on what Tewkesbury had written, taking it even farther. And musically, her performances are among the highlights of the film. Michael Murphy is appallingly confident and cool as a political hustler who’s laying the groundwork for his candidate’s campaign. He’s everybody’s friend, smiling and shaking hands, saying whatever’s necessary to get what he needs.

There are many other fine performers in the film, but it would take forever to give them all their due. Briefly I’ll say that Barbara Baxley, Ned Beatty, Karen Black, Keith Carradine, Robert Doqui, Barbara Harris and Lily Tomlin are all outstanding. And aside from playing their individual parts, they work together beautifully. Altman was known for making films that utilized a large cast of characters, and this is one of the finest ensembles he ever worked with.

In Nashville Altman presents a sweeping landscape of American music, American culture, American life. Though at times he seems to be filled with bitter cynicism, it’s clear he also has tremendous love for his country. The movie is shaped by this conflict, and Altman doesn’t try to resolve it. At the end of Nashville, a crowd of people that has just witnessed a tragedy comes together in song, lifting their voices with the performers on stage to affirm that they will keep moving forward no matter what. However the song’s refrain, “You may say that I ain’t free, But it don’t worry me,” is deeply disturbing. Is it that they aren’t paying attention to the lyrics? Or is it that they really don’t care?

Altman lets you decide what it all means. The camera pans slowly upward, away from the crowd, and the voices fade as the sky fills the frame.

The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death is a brief, terrifying parable. Prospero is a wealthy prince whose land is being ravaged by a plague. He gathers his aristocratic friends together in a castle and seals it tight to keep them all safe from the disease. Believing that they now have nothing to fear, Prospero and his guests devote all their time to extravagant entertainments, while those left outside face certain death. But like a story in the Old Testament, The Masque of the Red Death ends in terrible retribution. Prospero and his friends learn that no walls are thick enough to save them from the plague.

When I went back to story and re-read it, I was surprised to find that Prince Prospero is the only character mentioned by name. Poe spends little time describing the man himself, and he only speaks a few lines of dialogue. Most of what we learn about Prospero comes through the author’s description of the apartments designed by the prince, a suite of seven rooms, each decorated in a single color and lit by torches that shine through colored glass. The scene that Poe paints for us is highly stylized, almost abstract. Really it’s the landscape of the mind.

To make a feature length commercial film, director Roger Corman obviously had to flesh out the material. This can be a dangerous proposition, because often the whole effect of a short story depends on its brevity. But Corman was a lifelong admirer of Poe’s work, and he knew that he couldn’t just add padding to the author’s tale. The screenplay would have to expand on the material in such a way that it grew organically from Poe’s original concept.

Corman has said that in his Poe adaptations his preferred approach was to use the original story as the third act, the climax of the film. That’s what he does here, and the screenwriters do a beautiful job of fleshing out this macabre little tale. The script, by Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell, expands on Poe’s story a good deal, and yet it stays essentially faithful to the author’s conception. In addition, Beaumont and Campbell bring in fragments of another Poe story, Hop-Frog, weaving it skillfully into the framework of the film.

What the screenwriters do with Prospero is pretty impressive. Starting with the minimal details that Poe offers in the story, they create a fascinating, multi-faceted character. This is not your standard horror movie villain. Prospero is a philosopher who sees the world in the bleakest possible light. He is horribly cruel, but he is also intelligent, thoughtful and sensitive. This is a man who has spent his life observing the world, seeing the horror and misery that plague mankind, and he has become brutally cynical. He refuses to believe in a loving God, because he can’t believe that God would allow the suffering and the violence he’s witnessed.

As the film begins, we see Prospero’s cruelty in the harsh punishments he inflicts on the peasants in a small village. But as the story unfolds, we learn that he has no more respect for his fellow aristocrats than he does for the peasants. He sees his guests as weak and foolish, and he takes joy in humiliating them. He’s appalled by humanity. It’s as though he’s punishing mankind for its cowardice and stupidity.

Prospero is a frightening, fascinating character, and the part would be a challenge for any actor. Fortunately, Corman turned to Vincent Price, who he’d already worked with on a number of films. Price is magnificent. His performance is a marvel of intelligence and subtlety. Prospero is repellent, and yet at the same time we can’t take our eyes off him. Playing the part, Price commands our attention, but without unnecessary theatrics. Graceful and witty, cold and merciless, the actor’s performance as Prospero is one of his finest.

Art director Robert Jones and production designer Daniel Haller create an oppressive, expressionistic world that reflects the disturbing beauty of Poe’s writing. A young Nicolas Roeg shoots it all with striking confidence. The richness and subtlety of Roeg’s lighting gives the images dimension and depth. By this point in his career Corman was very assured as a filmmaker and he seems to have an intuitive understanding of the rhythm and shape of a scene. His camera glides through the chambers of the castle, settling on one composition, shifting to another, defining the relationships between the characters and heightening the tension.

Sound also plays an important part. Striding through an eerie silence, Prospero lectures his guests on the terror of time, the ticking of a clock in the background, the soles of his shoes clicking against the marble floor. Francesca is wakened in the middle of the night, and as she peers through the dark bedroom we hear the flutter of birds’ wings receding into the night, suggesting a phantom in flight. In keeping with the way Poe uses words, Corman uses images and sounds not just to create a physical world, but also a psychological landscape.

I often hear people make excuses for crude, shabby horror movies. They didn’t have the money. They didn’t have the time. Roger Corman proved over and over again that limited resources are no excuse. With a little creativity and cunning, a filmmaker can work wonders, even if they’re shooting on a shoestring. It’s not the size of your budget. It’s the size of your imagination.

Too Much Johnson (1938)

I just got back from seeing Too Much Johnson at LACMA, and I’m not sure if I can describe the way I feel right now. Excited and grateful are two words that come to mind, but that’s just scratching the surface. I feel like I’ve been allowed to look through a window on the past. I feel like I’ve travelled back in time and caught a glimpse of a brash young man who was crazy enough to think he could conquer the world.

I just got back from seeing Too Much Johnson at LACMA, and I’m not sure if I can describe the way I feel right now. Excited and grateful are two words that come to mind, but that’s just scratching the surface. I feel like I’ve been allowed to look through a window on the past. I feel like I’ve travelled back in time and caught a glimpse of a brash young man who was crazy enough to think he could conquer the world.

No doubt my reaction has a lot to do with the tremendous respect I have for Orson Welles. It’s not just that I think he’s a great director. I feel closer to Welles than any other filmmaker. His work literally changed my life. So to have this footage surface out of the blue when everybody thought it was long gone is pretty amazing.

It’s important to say at the outset that Too Much Johnson was never intended to be released as a feature. Welles wanted to present William Gillette’s play on the stage, and the production he envisioned included film segments that would introduce each act. He shot four hours of footage and began to edit it, but the play didn’t survive out of town tryouts and the partially completed fragments were never shown. Apparently the reels sat in a warehouse for decades until they were recently rediscovered.

The surviving material is over sixty minutes of film that was partially edited by Welles. Of those sixty minutes, only about the first third approaches anything like a coherent narrative. The rest is comprised of disconnected scenes in some kind of sequential order, but remember that this was never meant to be a complete narrative anyway. What we’re seeing are fragments of fragments. In some cases we see multiple takes of a single shot, and at times it’s hard to make any sense of what’s happening onscreen. Many people would probably see this stuff as an incoherent mess. Apparently some audience members who have viewed the footage were disappointed. I guess it depends on what you’re looking for.

I was thrilled. Not because it’s up there with Welles’ best work. It’s certainly not. But it’s a glimpse of one of film’s great artists at a time when he was first getting a grip on the medium. And in spite of the incomplete and chaotic nature of what remains, it clearly points toward the work Welles would do when he came to Hollywood.

To this day, many people look at Welles’ career and see a failure. They complain that he worked intermittently as a director, couldn’t adjust to the demands of the studio system and left many projects unfinished. No doubt the appearance of one more unfinished film will be seen by many as further evidence of his “lack of discipline”. What rubbish. The idea that somebody who completed thirteen features, often using his own money, could be called undisciplined is ridiculous. Obviously Welles’ critics have absolutely no idea how difficult it is to make a movie, much less how incredibly difficult it is to make a movie on your own terms. These people also ignore the fact that Welles staged several plays, created a small but startling body of work for television, and produced a staggering number of broadcasts for radio.

He didn’t finish everything he started. That’s true. Welles had a restless mind and was constantly looking for new challenges. Sometimes he took on more than he could handle and found himself running short of time or money or stamina, and yes, he had his share of colossal failures. So what. I’m way more interested in somebody who shoots for the moon and fails than I am in somebody who plays it safe and “succeeds”. Welles liked to take chances. He liked to test the boundaries. He liked to experiment.

Too Much Johnson is an experiment. Watching the footage it was as though I could feel Welles’ excitement in discovering film. In the early scenes especially I got the sense that Welles was playing with the medium, trying to see how far he could go. A couple of the people who spoke at the screening I attended said that Welles was trying to recreate the look of the films made between nineteen ten and nineteen twelve. I couldn’t disagree more. In movies from that period scenes were almost invariably shot from a single angle, usually frontal, and cutting within a scene was rare. Close-ups were almost non-existent.

Too Much Johnson, on the other hand, is strikingly dynamic. Welles’ forceful compositions anticipate Citizen Kane, and the only silent film directors you’ll find who take the same liberties in framing a shot are the guys who made avant-garde shorts in Europe during the twenties. Even before he got to Hollywood, Welles already had a strong visual sense. He was always looking for ways to create space. And in the sequences that are most fully shaped, there is a good deal of cutting, some of it so bold and so rapid that you might compare it to Eisenstein.

Apparently Welles watched a lot of silent comedy to prepare for shooting, and no doubt Mack Sennett was an inspiration. But the complexity of the best gags and the imaginative imagery are way beyond the crude, knockabout antics of the Keystone Cops. Too Much Johnson is closer to the inspired surrealism of the films Buster Keaton made in the twenties.

Seeing Too Much Johnson is a reminder of how much Welles loved comedy. Because our view of him today is based mostly on the features he made, I think that’s an aspect of his work that tends to be forgotten. While most of his films have comic moments, the context is often so dark that I rarely laugh out loud. But look at the plays he staged on Broadway, like Horse Eats Hat and Shoemaker’s Holiday. Listen to his radio adaptations of Life with Father and Around the World in 80 Days, or the variety shows he did in the forties. Check out The Fountain of Youth, a witty and inventive TV pilot he made in the fifties. Welles loved a good laugh, and Too Much Johnson reminds us that he spent a lot of time trying to make audiences laugh, too.

I think one of the reasons that Welles left a number of projects unfinished is that he expected a lot of himself. When you look at the time he invested in preparing his films, the energy he expended in shooting his films, and then the obsessive care that he took in editing his films, it’s clear that he had extremely high standards. Those of us who value his work can’t help but feel frustrated that we never got to see Don Quixote or The Deep. But my feeling is that he didn’t finish them because he wasn’t satisfied with them. In his mind, they weren’t good enough.

If that’s true, he’s probably rolling over in his grave now that this footage from Too Much Johnson has been discovered. It’s rough, it’s raw, it’s messy. But for those of us who love Welles, it’s a reminder of how talented, how daring, how creative the guy was. It’s exhilarating to see the way he threw himself into shooting this footage, back when it probably seemed like anything was possible. Back when he was still a brash young man who was crazy enough to think he could conquer the world.

*

There were many people involved in bringing Too Much Johnson to the screen. One of the most important players was the National Film Preservation Foundation. They’ve been responsible for the rescue and restoration of many movies thought to be lost, and if you care about film history, you might want to think about making a contribution. Just click on the link below.

Duck Soup (1933)

It would have been impossible for the Marx Brothers to make their early films anywhere besides Paramount. Many comics make us laugh by showing us their struggles as they try to keep up with the world. With the Marxes, we laugh as we watch the world struggling to keep up with them. At their best, they come across as manic madmen who get their kicks by trashing every convention that society holds dear. They needed to inhabit a world of their own, a world where they could gleefully shred the rule book and get away with it. Fortunately, Paramount allowed them to do just that. In the thirties the studio was known for producing eccentric fantasies like Million Dollar Legs, Alice in Wonderland and If I Had a Million.

The Marx Brothers didn’t write or direct their own movies. They had to depend on others to create the right setting for their antics, and it wasn’t easy to find people who understood them. Even in their films at Paramount you can see that the writers and directors behind the camera couldn’t always figure out what to do with them. The first two are basically filmed stage plays. The next two, while much more dynamic, are fairly chaotic and haphazard. The only one that totally works as a film, that has a look and a style and a rhythm, is Duck Soup. And that’s mostly because it was directed by Leo McCarey.

Leo McCarey understood film. His style was simple and direct, but at his best he had a wonderful gift for catching performers at their most relaxed and spontaneous. McCarey had supervised some of Laurel and hardy’s best silent films, often starting with a simple premise and making the movie up as he went along. He knew how to improvise. You can tell by watching his films that he’s willing to take the time to let the actors find their own rhythm. He had no problem letting go of the script and allowing the film to develop on the set.

Which is not to say that McCarey put Duck Soup together all by himself. According to Joe Adamson, Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby wrote the first draft. Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin are also credited, but there were others involved as well. It was standard practice in those days to hire as many gag writers as you thought were needed to keep the laughs coming. But Adamson also says that McCarey made some major additions during shooting. He cites the mirror scene, the street vendor dust-up and an extravagant musical number, none of which appear in the final draft of the screenplay.

Though Duck Soup makes merciless fun of politics, it falls less into the realm of satire than surrealism. Groucho arrives at his inaugural ball by sliding down a fire pole. Harpo walks around with a pair of scissors, randomly cutting up ties, cigars and feathers. But there are some scenes with a sharp satirical edge, most notably the musical numbers. As soon as Groucho takes over as president of Fredonia, he outlines his plans for the country by singing a song….

If any form of pleasure is exhibited

Report to me and it will be prohibited

I’ll set my foot down, so shall it be

This is the land of the free

And at the moment when Groucho finally declares war, he and his brothers lead the people of Fredonia in a freewheeling musical parody, with the entire gathering raising their voices to sing the line, “All God’s chillun got guns.”

It’s not just the Marx Brothers who are in top form here. Duck Soup boasts a splendid supporting cast. Louis Calhern is perfect as the suave diplomat Trentino, putting out just as much energy as the Marxes and displaying a sharp sense of comic timing. As Trentino’s spy, Vera Marcal, Raquel Torres slips smoothly between her roles as conspirator and confidante. Margaret Dumont plays Margaret Dumont beautifully. In Coconuts and Animals Crackers Groucho’s antics might provoke her scorn or censure. In Duck Soup she seems oblivious to his barbs. Groucho is courting her one minute, insulting her the next, and she just takes it all in stride.

Duck Soup was the peak for the Marx Brothers, and from there on it was all downhill. They left Paramount and moved to MGM, where Irving Thalberg convinced them they’d do better if their films had a story with a love interest and higher production values, the upshot being that they became supporting actors in their own movies. After Thalberg’s death, they were consigned to routine vehicles that rarely allowed them to be themselves. The producers who handled their subsequent films apparently saw the Marx Brothers as just another comedy team.

But one of the great things about movies is that they can capture performers at the height of their powers. We’re lucky the Marx Brothers made the transition from stage to film. We’re lucky they had a few good years at Paramount. And we’re especially lucky that they teamed up with Leo McCarey. Whatever came later, we’ll always have Duck Soup.

*

For anyone interested in finding out more about the Marxes, you can’t do better than Joe Adamson’s Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo. Adamson talked to a lot of the people who worked on their movies and his research in general is really thorough. He’s an engaging, insightful writer, and on top of all that he’s funny. The book has been out of print for years, but it’s easy to find copies on the internet. I recommend it highly.

Espaldas Mojadas [Wetback] (1955)

Mexicans have been crossing the border to work in the United States since the border was drawn back in the nineteenth century. Many make the trip to escape poverty or persecution, hoping to find a better life. There are some success stories, but the vast majority end up working long hours for subsistence wages. Those who don’t have the papers they need to work legally get stuck in exhausting, low-paying jobs, and often the employers who know they’re stuck take full advantage of the situation.

One of the most powerful films I’ve seen about those who make the crossing is Espaldas Mojadas by Alejandro Galindo. While the story is driven by melodrama, and the director makes his points forcefully, the film also has a haunting sadness that stays with you long after it’s over. This isn’t just a movie about a guy who’s trying to make a living and stay ahead of the law. Espaldas Mojadas is about the painful loneliness and crushing isolation that people feel when they have to leave their home behind.

The film begins with a lengthy disclaimer explaining that it has nothing to do with the US/Mexico border, and that in reality it’s about people who break the law and the consequences they must suffer. It’s all totally bogus, of course, but it’s a sign of how worried the Mexican film industry was about offending American audiences. The US market was vital for the Mexican producers, and the fear of losing that market was always hanging over their heads.

The story opens in Ciudad Juárez, where we find a man, Rafael, desperately looking for a way to cross the border. He’s in trouble with the law and needs to disappear quickly, but he doesn’t have the papers he needs to enter the US legally. Rafael makes a deal with a coyote who takes him across the Rio Grande into Texas, but this is just the beginning of his troubles. He finds work, but his American bosses use him and abuse him. And if he gets fed up and leaves, then he’s back at square one and has to go begging for a job all over again.

Espaldas Mojadas is a lament for all those who’ve been trapped in the US while their hearts are still in Mexico. Though Galindo relies heavily on melodrama, the film doesn’t treat Rafael’s plight as an excuse for action. The director spends a good deal of time with his characters, allowing us to get inside of them. For me it’s the quiet moments that are the most affecting. Rafael standing by the railroad tracks as he talks to a friend about how it feels to be lost in a strange country. A Mexican border official scolding Rafael for working illegally in the US, and then falling silent as his prisoner tells him about the desperation that drove him to do it. But the most beautiful and haunting scene takes place in a work camp where the men have been laying tracks for the railroad. They have a day off. They’ve been breaking their backs all week long, and now they’re lounging under the railroad cars to stay out of the sun. A man with a guitar starts to play, another starts to sing. The song is Canción Mixteca by José López Alavez, and it’s about the loneliness felt by those who are far from home. The camera tracks past the men as they listen, and in this melancholy moment Galindo crystallizes the sadness they feel and their longing for the country they’ve left behind.

While there’s a good deal of music in the film, the underscoring is provided by nothing more than a single guitar, and this was exactly the right choice. Instead of having a full orchestra to pump up the drama, we have a single musician providing a very spare and very effective backdrop for the story. The lonely tones of the solo guitar match Rafael’s sense of isolation perfectly. At the other end of the spectrum, there’s a thrilling performance by Lola Beltrán and El Trío Calaveras at a bar in Ciudad Juárez. They set the crowd on fire with their passionate rendition of a song about the pride they feel in being Mexican.

Unfortunately, this film, like so many other Mexican films from the same era, is only available as a budget DVD. The print is okay. The transfer is acceptable. But there are no subtitles, which is probably going to keep anyone who doesn’t speak Spanish from watching it.* I’ve written before about the challenges of trying to preserve Mexico’s cinema. I know the list of films that need attention is long, and the money available is short. But is it too much to ask for a quality DVD release of a classic film by a major director from Mexico’s golden era?

Is anybody at Criterion listening?

*

Honestly, Galindo is very good at communicating through images, and I think most people could follow the story even without subtitles. You might miss some of the plot points and some of the humor, but I still urge you to give it a try. It’s a powerful experience.