Secret Agent (1936)

When people talk about Alfred Hitchcock’s career before he came to the US, they generally talk about The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes. Those are the two films that get all the attention, and the rest of his work in Britain is pretty much forgotten. But Hitchcock made over twenty features before he came to the US, and these are the movies that laid the groundwork for his whole career. Many of the themes that run through Notorious, North by Northwest, Vertigo and Psycho are already apparent in the films he did in Britain.

Hitchcock’s earliest work in the silents is wildly uneven, but by the time sound came in he seemed to have a pretty good idea of where he was going. It’s also interesting to see him play with the medium and test its boundaries. Blackmail may not be up there with Hitchcock’s best, but in some ways it’s really innovative, and you can already see the director’s grim sense of irony. Sabotage tells the harrowing story of an ordinary woman who’s caught up in an extraordinary situation, an idea that Hitchcock returned to many times in later years.

Secret Agent is one of the most complex and disturbing films the director made in Britain. Based on W. Somerset Maugham, the film tells the story of an inexperienced spy who finds himself getting cold feet when confronted with the ugly realities of his job. It’s one of Hitchcock’s most confident early efforts. He was lucky to have a strong script by Charles Bennett and Ian Hay, providing a fast-paced story and witty dialogue. This is one of the earliest films that exhibited the unique mix of suave sophistication and unnerving anxiety that would serve the director so well throughout his career.

Most spy movies start with the assumption that the hero is working for the good guys, and so anything he does is justified. Not so in this case. While the producers may have seen the film as pro-British propaganda, Hitchcock undermines that agenda by showing the awful complexities that confront a spy during wartime. There are few espionage movies that allow the hero to kill the wrong man, but that’s exactly what happens here. Our hero, Ashenden, and his associate, the General, believe they’ve found the enemy spy and arrange for him to have a fatal accident. But they’ve guessed wrong, and a kindly middle-aged man is sent to his death. The director makes us feel the pain of this senseless loss by letting us hear the man’s dog wailing uncontrollably after he’s gone.

At this point Ashenden is starting to question the whole enterprise, and Elsa, who’s been posing as his wife, is convinced they need to call it off. The General, meanwhile, is determined to finish the job, and wastes no time grieving over the innocent man’s death. This sets up the tension that underlies the rest of the film. Elsa is adamant that murder is immoral, whatever the reason, and has no intention of continuing. The General, on the other hand, is a hired assassin who’s always ready to ply his trade. And Ashenden is caught between the two, appalled at the General’s callousness, but believing he’s got to do his duty, no matter how difficult it is.

John Gielgud gives a strikingly sharp performance in the title role. At first smart and suave, we see him turn anxious and indecisive when it comes down to actually taking someone’s life. Madeline Carroll is also excellent. She’s not just playing the love interest. Her character starts with the attitude that the spy game is an amusing romp. After the death of an innocent man, she realizes how terrible the consequences can be. As the enemy spy, Robert Young demonstrates what a gifted actor he was, with a deft touch for comedy, but also the ability to project a ruthless cool. It’s a shame he wasted the later part of his career in saccharine TV shows. Peter Lorre was a marvelous actor, but I have to say he’s a little too much for me here. His performance is enjoyable, but it’s too insistently eccentric. I think I’d like him better if he’d taken it down a notch or two.

After the big climax, the film’s final scenes show a quick montage of the Brits winning the war, followed by a shot of Ashenden and Elsa, now reunited as a happy couple. It’s way too pat. This facile wrap-up brushes aside all the nasty aspects of the story we’ve just watched in order to send us away with a happy ending. But Hitchcock has begun his exploration of the awful uncertainties, the disturbing ambiguities that all of us have to deal with in one way or another. As his career continued, this journey would take him into some of the darkest corners of the human soul.

Blackboards (2000)

You won’t find Kurdistan on the map. But it’s very real to millions of Kurds. The region they live in has been battered by conflict for centuries, and the boundaries have shifted over and over again. After WWI Kurdistan was divided up among four neighboring countries, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Somehow the Kurds have managed to hang on to their culture and their language in spite of this. In some areas they’ve even gained a fair amount of political and economic clout. But there are also large numbers of Kurds who live as nomads, wandering through the countryside. This life has always been difficult. In recent years, with violence erupting all over the Middle East, it has become nearly impossible.

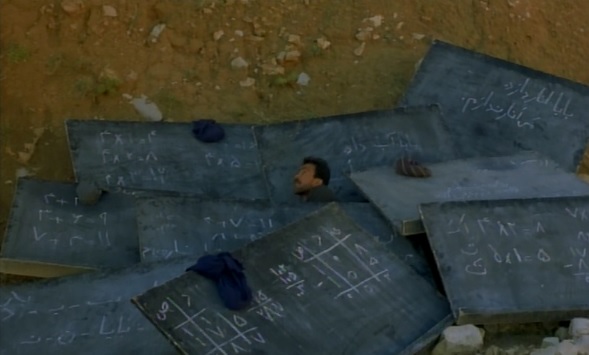

In her film Blackboards, Samira Makhmalbaf focusses on the Kurds who spend their lives travelling on foot through a harsh and desolate landscape. The story revolves around two teachers who are wandering across the mountains of Iran, hoping to find someone who will pay them for lessons. One runs across a group of boys who are smuggling contraband. The other falls in with a band of nomads who are lost in the wilderness. It turns out all of them are trying to cross the border into Iraq.

It’s clear these people lead hard lives, but those of us who have always had food on the table and a roof over our head probably can’t ever imagine how much suffering they’ve endured. Makhmalbaf slowly reveals pieces of their history, giving us glimpses of the violence they’ve been subjected to, but she’s not trying to win our sympathy. She’s not trying to bring tears to our eyes. Instead, she’s opening a window on the world these people live in.

Makhmalbaf somehow manages to combine rigorous objectivity with breathtaking poetry. She’s a born filmmaker.* She seems to have an intuitive understanding of sound and image. Blackboards is wonderfully simple. We follow two groups of people walking across a barren landscape, watching their faces, listening to them talk. The mountains and valleys that stretch across the horizon, dwarfing these frail travellers, have a stark, surreal quality. They seem both brutally harsh and strangely ethereal. Makhmalbaf uses music sparingly, and so much of the time these people are enveloped by an enormous silence, broken only by the sound of footsteps, scuffling across the dirt, clattering over stones.

The teachers are trying to sell their services, but nobody wants them. For people like this who are struggling just to survive, the idea of wasting time on luxuries like reading and writing seems pointless. An so the teachers, who start out aggressively, insisting that everybody needs what they’re offering, end up becoming beggars, following these desperate people, hoping to earn a piece of bread. At first the teachers can’t even get anyone to talk to them. Both the smugglers and the nomads are deeply suspicious of strangers. They have good reason to be. The boys make their living by acting as mules, carrying contraband across the border, trying not to get shot in the process. Having lived longer, the nomads have suffered more. They’ve persevered through years of conflict between Iran and Iraq, as well as two invasions by the US. The lone woman in the tribe is sullen and stoic. Even after marrying one of the teachers, she answers his questions in single syllables. Later we learn that she’s one of the few who survived when Saddam Hussein bombarded the city of Halabja with chemical weapons. She has no patience for useless talk. She’s too busy trying to make it through another day.

And that’s all the teachers are able to do. At the end of the film, they have nothing to show for their efforts. Border guards fire on the child smugglers, and the boys run for their lives. The nomads manage to cross into Iraq, but the teacher who was travelling with them chooses to stay behind. His divorce from his wife is as simple and quick as their marriage. And she walks off toward the horizon, carrying his blackboard with her.

*

The fact that she’s the daughter of Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf might have something to do with it. Maybe it’s just in her blood.

If You’re Gonna Show 35….

A few weeks ago I went to the New Beverly to see some movies. I actually saw two separate screenings, a Sam Peckinpah double bill and a William Witney double bill. I want to start by saying that I appreciate Quentin Tarantino’s commitment to showing films in 35mm (or on occasion 16mm). Digital is fine, and given the economics of distribution and exhibition, there’s no way we’re going back. But it’s important to remember that, from the beginning of cinema history up until just recently, film was the standard, and that 35mm is an excellent medium for projecting an image on a screen.

That is, if you’re using a decent print. If the print’s not in god shape, you can run into all kinds of problems, and that’s why I’m writing this post. For the Witney bill, they showed Master of the World and Stranger at My Door. Stranger at My Door looked good. The print was in good condition, and it was a pleasure to see it on a big screen. On the other hand, Master of the World looked awful. The print was still pretty crisp, but the color was completely degraded, to the point where the whole movie looked pink. I doubt William Witney would have been happy if he’d been in attendance that night.

The Peckinpah bill was worse. I guess you could say the print they showed of The Getaway was acceptable, but it obviously had a lot of miles on it. Watching Junior Bonner, though, I got angry. The color was so bad, I’m not even sure you could call it color. It looked as though somebody had dumped the reels in a bathtub full of bleach. This is not the way the movie was meant to be seen.

It was especially frustrating because I loved the movie. I’d never seen Junior Bonner before, and it’s definitely one of Peckinpah’s best. Those who know him only for his action flicks don’t fully understand who he was as an artist. Junior Bonner is a low key film about a fading rodeo star who rolls into his hometown and reconnects with his family. It’s a beautiful character study, the cast is great, and Steve McQueen is especially impressive.

I’m glad that Tarantino is programming stuff like this, but he really needs to find better prints. Aside from my personal frustration at seeing a print so badly faded, I wonder what impression this gives younger viewers of 35mm. What would somebody in their early twenties think watching the Peckinpah double bill? They’d almost certainly come away with the impression that film was an inferior format, and that they were lucky to be living in the digital age.

Revival houses have always had to struggle to get decent prints, and these days it’s probably harder than ever to show movies on film. It’s great that Tarantino has a huge private collection, but he’s not doing anybody a favor by showing stuff in this condition. Older audiences will be frustrated. Younger audiences won’t get a chance to see these movies the way they were meant to be seen. And I think many filmmakers would be furious at the way their work was being presented.

So if you’re gonna show 35, it’s gotta be good 35.

The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Russian culture was a hotbed of innovation. In constant conversation with Europe, Russian painters, writers, musicians and filmmakers were rapidly absorbing new ideas from France, Italy and Germany, and blazing new trails of their own.

When the Revolution occurred in 1917, it only seemed to add fuel to the fire. Artists were called on to promote the creation of a new social order, and many of them responded enthusiastically. But there was a shift in direction. Now the ideal was not art for art’s sake, but art that served the people. And so the photographer Alexander Rodchenko began designing posters and packaging. Liubov Popova went from creating paintings to creating textiles. Vladimir Tatlin, known for his abstract constructions, was commissioned to build a monument to the Revolution.

Film was to play a key role in educating people about communist concepts. Since much of the population was illiterate, it was important to communicate the ideals of the Revolution without words, and film had proven its potential as a tool for propaganda. Initially filmmakers were encouraged to experiment, and people like Eisenstein, Vertov and Dovzhenko created visually dazzling features that celebrated the common man.

Among this group of innovators was Vsevelod Pudovkin. In 1927, on the tenth anniversary of the Revolution, he directed The End of St. Petersburg to commemorate the overthrow of the Tsar and the transition to a new society. The story is blunt propaganda. It tells us how the simple, honest workers rise up to defeat the soulless, corrupt capitalists. A starving farm boy comes to St. Petersburg looking for work at a factory. Hoping for help, he calls on a friend, but the friend’s wife says she has nothing to offer and turns him away. When a strike is called at the factory, he jumps at the chance for a job without realizing what he’s getting into. Caught in the middle of a chaotic situation, confused as to what’s going on, he fingers one of the strike’s leaders, who is then arrested. Realizing what he’s done, the boy sets out to correct his mistake, but runs up against the evil oppressors and is thrown in jail.

In the hands of a lesser director this would be a dreary tract. But Pudovkin takes simplistic propaganda and creates an epic canvas populated by mythic characters. And somehow, even though the characters are all archetypes, the director makes them searingly human. Much of this is because of the way Pudovkin handles the actors. In the first place, these are not movie stars. They look like ordinary people. The faces of the peasants on the farm are weathered and worn. It’s not hard to believe they’ve been ploughing these desolate fields for years. When tragedy strikes, the actors don’t dramatize their pain. Instead they confront suffering with a weary stoicism. It’s as though a life of backbreaking labor has robbed them of their emotions.

But Pudovkin doesn’t just speak through his actors. He also speaks through images. The film is a blistering visual poem. When we arrive in the city, Pudovkin doesn’t just show us a factory. He creates a montage that assaults us with the terrifying energy and sweltering heat of the Industrial Age. Giant steel wheels spin, vats spill streams of molten metal and chimneys spew vast clouds of black smoke into the sky. The workers are scorched and spattered. They look as though they’ve been pushed to their limits. And so when the factory manager insists that they put in more hours, they refuse. They’ve had enough.

A strike is called. The capitalists crush it. The boy from the farm and the leader of the strike are made soldiers and sent to fight the Germans. But rather than making the war sequences about their struggle for survival, The End of St. Petersburg takes a completely different approach. The horrific images of violence and death are intercut with scenes of stock market traders frantically buying and selling their shares. Prices climb higher and higher on the exchange as the body count rises on the battlefield. When the fighting is over, the titles tell us, “The transaction is completed. Both parties are satisfied.”

Most propaganda films end on a celebratory note. Here the final scenes are muted. The revolutionary forces overthrow the monarchy, but at great cost. After the battle is won, the soldiers who fought to take the Winter Palace are tired and hungry, on the verge of exhaustion. The woman who had turned the boy away earlier comes to the Winter Palace looking for her husband. As she climbs the steps, she comes across the boy, lying on the ground, wounded and weary. Though she sent him away earlier, now she kneels and holds him in her arms. Knowing he must be hungry, she gives him the little food she has left, a handful of potatoes. This simple, caring gesture is more powerful than any revolutionary slogan, any celebration of the workers’ triumph. Pudovkin may have been making propaganda, but ultimately he was more interested in people.

This brief period of astounding creativity in Russian cinema was short lived. As Stalin consolidated his power, he exerted more and more control, not just over filmmakers, but also writers, composers and other artists. The idealism that had lifted them to new heights, that had inspired them to make revolutionary art, was crushed. It would be decades before Russian cinema found its voice again.

Moonstruck (1987)

John Patrick Shanley is such a generous writer. He loves his characters, and he wants to immerse us in their world. While at first glance they may seem petty, foolish, unreasonable, as we get to know them better we realize that they’re driven by the same desires, the same fears, as the rest of us. They may be flawed, but so is the rest of humanity.

Moonstruck is a richly detailed comedy about a woman approaching middle age, Loretta, who falls in love with her fiancé’s brother, Ronny. The premise is familiar, but Shanley takes us beyond the predictable complications of romantic comedy. He brings us into Loretta’s home to meet her mother and father, who have their own marital complications. We meet her grandfather, who walks his pack of dogs and worries that his family is unhappy. We sit down with everyone at the dinner table, where the in-laws tell stories about early courtship. Rather than just focussing on Loretta and Ronny, Shanley looks at the troubled relationships of the people around them. In most romantic comedies we take it for granted that the couple is in love, and the movie is about the hurdles they have to jump to be together. Moonstruck asks what love is, and the answer isn’t simple.

Nothing is simple in Moonstruck, least of all the families. Loretta’s fiancé Johnny is a mama’s boy, flying off to Italy to visit the woman who gave birth to him one last time. Loretta’s love for her father is tempered by the fact that he refused to give her away when she was first married. Ronny bears a burning grudge against his brother, believing that it’s Johnny’s fault he was maimed. The film shows how all these people are products of the relationships they have with their parents, their siblings, their children, both for good and for bad. In fact, the good and bad are inseparable. Loretta and Ronny can’t just ride off into the sunset together because they’re completely tangled in the complicated web that families weave.

Many of these people are driven by desire. The characters are either burning with it, or they’ve been burned by it. Loretta’s father, Cosmo, woos his mistress, trying to pretend he’s a young man again. His wife, Rose, lies in bed, frustrated that her husband won’t touch her. A college professor dates a string of young students, trying to rekindle his interest in life. And Loretta, who hasn’t been with a man since she was widowed, suddenly finds herself throwing caution to the wind and letting Ronny sweep her off her feet.

But desire is tempered by awareness of death. As he walks into the kitchen, Loretta’s father echoes Vicki Carr singing, “Or I will die….” The grandfather meets his ancient friends in a cemetery where they stand together over a grave. Ronny and Loretta go to the Met to see La Boheme, a story about lovers separated by death. As these people eat and drink, argue and make love, mortality is always standing in the background. When Loretta’s father criticizes her engagement ring, she responds by telling him it’s temporary. He shouts back at her, “Everything is temporary!”

Director Norman Jewison handles the intricate script with admirable assurance, breathing life into the people that Shanley has created. Jewison has an impressive grasp of the craft of filmmaking, but he’s more than just a craftsman. At his best he imbues his work with a vibrant energy and an exhilarating expansiveness that can carry you away. In Moonstruck the warmth of his images makes palpable Shanley’s love for his characters. And he makes New York glitter. Much of the film is shot on location, and the characters seem to really belong on these streets. Jewison took great pains to capture the community that the story takes place in. As an example, the director felt it was so important to have his actors experience the heat and the smell of a real bakery that he changed the last name of Ronny’s character to fit an actual bakery that he felt was perfect for the scene. While the film is part fairy tale, this insistence on rooting it in actual experience gives it weight and texture. Jewison is lucky to have the gifted David Watkin as cinematographer. His attention to light makes the streets, the shops, the homes all feel alive. Watkin’s work with the actors is even more impressive. He doesn’t just photograph faces, he photographs feelings.

The lovers end up together, but Shanley doesn’t tie everything up in a neat little bow. Frustrated by Loretta’s resistance, Ronny tells her, “Love don’t make things nice. It ruins everything.” Shanley doesn’t believe that relationships are about looking for happy endings. Ronny goes on to say, “We are here to ruin ourselves, and to break our hearts.” And in the end, Loretta acquiesces. She accepts the messy, crazy chaos of life.

But at the end, the film doesn’t focus on the lovers. In the last scene everyone is gathered around the breakfast table, parents, siblings, in-laws, and they drink a toast to the family. In spite of all the pain, anger, guilt and shame that goes with those relationships, Shanley seems to be saying that the good outweighs the bad. He still embraces the family.

No Blood Relation (1932)

Back in the first half of the twentieth century, Japan had a studio system that was comparable in many ways to Hollywood. And just like in Hollywood, the Japanese studios churned out genre films by the dozens. These were films based on formulas that had proven appeal, using melodramatic plot lines that generally followed well-worn patterns. They were meant to be predictable.

But just like in Hollywood, there were directors working within the system who would take this conventional framework and somehow manage to make something that undermined the conventions. One of these directors was Mikio Naruse. Over a period of four decades he turned out scores genre films, primarily women’s pictures and family dramas. But within what seems like a fairly narrow range of subject matter, he was able to tell stories with tremendous depth and subtlety.

No Blood Relation is basically a Shirley Temple movie.* It has the same melodramatic plot centered on a cute little moppet who is taken away from the woman she believes to be her mother. But the complexity of the relationships and the depth of feeling takes No Blood Relation way farther than any movie Shirley Temple ever made.

Naruse focussed on women throughout his career, and here it’s the women who are at the heart of the story. We have Tamae, who years ago left her husband and her child to become a movie star. At the beginning of the film she returns to Japan to reclaim her daughter, Shigeko. But Tamae’s ex-husband has remarried, and his wife, Masako, has formed an unbreakable bond of love with her stepdaughter.

It’s the tension between these two women that makes the film compelling and powerful. Masako is a simple, humble housewife who is completely devoted to her stepdaughter. The character could have been an awful drag, but Yukiko Tsukuba plays it with such simplicity and clarity that she seems completely real. We don’t doubt that Shigeko is the center of her world, and it’s wrenching to see the child taken away from her. At the other end of the spectrum is Tamae, the woman who left her family to become a glamorous movie star. Many filmmakers would have made her a villain. Naruse makes her a smart, confident, complicated woman who’s been haunted by her decision to abandon her daughter. Yoshiko Okada digs into the role, keeping us with her every step of the way as she desperately tries to win her daughter’s love.

Naruse’s visuals are surprisingly dynamic. You’d think for a domestic drama he’d keep the camerawork low key. Instead, he’s constantly tracking in, tracking out and panning from side to side. The editing is also unusually imaginative, with its surprising rhythms and unconventional transitions. Honestly I feel like the director overdoes it a bit, but the style never interferes with the drama. His first priority is always keeping us engaged with the characters and deepening our understanding of them. Like many filmmakers, Naruse started his career making movies that tested the bounds of cinematic form, but later settled into a more serene, fluid style.

The film is closely tied to the time it was made. Like much of the rest of the world, Japan’s economy was on the skids in the thirties. One of the plot complications here is that Shigeko’s father goes bankrupt and is sent to prison. The family loses their house and all their belongings, leaving the mother to work in a department store in order to make ends meet. The return of Tamae adds a layer of Depression-era fantasy to the film. Here is an ordinary woman who has become a movie star and travelled to Hollywood. She arrives in Japan on a massive ocean liner, and is greeted by reporters and photographers. Even if they disapproved of Tamae’s actions, I think it’s likely that many Japanese women would have envied this wealthy, independent actress who seems to be in complete control of her life.

“Seems” is the key word here. In the end, Tamae fails to reclaim her daughter, and returns to America. This ending is in line with the traditional morality that’s been an integral part of commercial films since the silent era. Money can’t buy you happiness. The only true happiness comes through embracing family and accepting your lot in life. But Naruse doesn’t moralize. He doesn’t use Tamae’s defeat as an opportunity to render judgment. When Shigeko is returned to her home, Masako realizes how painful the moment must be for Tamae. In the final scene, the family races to the dock to say farewell to the actress as her boat leaves. They arrive just in time. The ship is pulling away from the harbor, and the family runs to the dock to wave goodbye. A minute earlier Tamae was unhappy because she didn’t see the child in the crowd below. Now the pain of seeing her is too much to bear, and she turns away.

——————————————————

*

I don’t mean to imply that this film was intended to capitalize on Temple’s popularity. No Blood Relation was made around two years before the American child star hit the big time.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Nicolas Roeg’s early films are mysteries. He wasn’t really telling stories. He wasn’t creating drama. In the seventies and eighties Roeg was exploring a new language, melding sound and image, breaking down time and space. I always felt that understanding his films was less important than experiencing them.

That may sound like some kind of mystical rubbish, and there were plenty of people who accused Roeg of being glib and flashy. But from Performance (1970, co-directed with Donald Cammell) to Bad Timing (1980), I think Roeg was really trying to let us see and hear things in a new way. It may not have always worked, but I never doubted his sincerity.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is one of Roeg’s most ambitious films. It tells the story of the spectacular rise and fall of Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who comes to earth and builds a vast financial empire based on startling new technologies. The film was adapted from a novel by Walter Tevis. (Tevis also wrote The Hustler, which was brought to the screen by Robert Rossen in 1961.) While the narrative mostly moves forward, Roeg and screenwriter Paul Mayersberg don’t feel bound by traditional storytelling conventions. There are sensual reveries where bodies drift through an empty void. At times we hear sounds that seem to be echoing across the centuries. Time and space aren’t fixed in Roeg’s movies. They’re unstable. Porous. We may get a momentary flash of something that hasn’t happened yet. Or suddenly a window will open on the long lost past.

Mayersberg’s film résumé isn’t long, but it’s really interesting. In addition to The Man Who Fell to Earth, he also wrote Eureka for Roeg. And he wrote the screenplay for the 1998 film Croupier. It’s clear from just those three titles that Mayersberg is interested in outsiders. The first two are expansive, mythic stories of gifted men who build an empire and then see it stolen from them. The third in some ways is the polar opposite, focussing on a man who wants to isolate himself from the world around him, seeking safety in self-effacing anonymity. But all three are stories of individuals struggling with society, and in each one the main character finds himself trying to deal with a world which is basically corrupt.

Roeg is also interested in corruption, but tends to focus less on the world and more on the individual. His characters are often searching for something, sometimes literally on a journey of discovery. Along the way they tangle with sex and death, which in Roeg’s world are always closely intertwined. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, Thomas Jerome Newton seems to be immortal, but he watches everyone around him age, becoming weak and fragile. And while Newton has a wife and children back on his home planet, he’s not immune to desire. He meets a maid in a hotel and soon they’re sharing the same bed.

Sex is a subject Roeg is very interested in, and The Man Who Fell to Earth is more explicit than any other mainstream film I know of from the time. In your standard Hollywood film, sex is almost always about love, and it’s usually reserved for the main characters. That’s not the way it works in Roeg’s world. Love may or not may not be involved, and even when it is, the lovers are never pure. They’re just as vulnerable as real people, feeling loneliness, fear, insecurity and desperation. In his films sex is truly intimate, and that intimacy carries with it all the perils it does in real life.

I’ve seen the film several times, but this is the first time it occurred to me that the three principal talents, Roeg, Mayersberg and Bowie, are all British. Watching it from that perspective, it seemed to be very much about a foreigner slowly drowning in American culture. At first fascinated, then addicted, then overwhelmed and appalled. When Newton arrives at his hotel room in the Southwest, he asks Mary Lou to bring him a TV. Then more TVs crowd into the room. Finally he’s sitting in front of a wall of television sets, all tuned to different channels, bombarding him with chaotic visuals and disembodied voices. He’s confronted with a manic, kinetic collage of machines and animals, sex and savagery. The sensory onslaught becomes so overwhelming that he flips out. When he finally shouts, “Leave my mind alone!” is it just Newton shouting, or are the filmmakers also making a comment on the suffocating effect of American pop culture?

The visual texture of the film is wonderfully rich and extremely intricate. Anthony Richmond’s cinematography takes full advantage of Brian Eatwell’s stunning production design. As editor, Graeme Clifford gives it all a seductive, hypnotic rhythm. The sound is equally complex, thanks to the efforts of Robin Gregory, Bob Jones, Alan Bell and Colin Miller. It’s also important to mention the electronic effects by Desmond Briscoe, who pioneered the use of electronic sound in Britain. And the music is a fabulous crazy quilt of old standards, rock n’ roll, bluegrass and avant garde, to which John Phillips, Stomu Yamash’ta and Duncan Lamont all contributed.

As his career went on, Roeg moved toward a more conventional approach to image and sound. He seemed to be rejecting the oblique, enigmatic style of his early years and embracing a more straightforward kind of storytelling. That’s fine. As people mature, the obsessions of their youth often fall by the wayside. But I keep returning to Roeg’s early work, and I don’t think it’s just a sentimental attachment. There’s something in those movies that keeps calling me back. His films from that time are disturbing, sensual mysteries. Don’t try to understand them. Just let yourself fall into them.

Trouble at Home

If you don’t live in LA, you’ve probably never heard of the New Beverly Cinema. Even if you do live in LA, you may never have been there. But for a small group of people who love film, the New Beverly has been a home away from home. I think I started going there back in the eighties, when it was run by Sherman Torgan. Sherman died several years ago, and since then his son Michael has taken over. For both of them, running the theatre wasn’t a job, it was an act of love.

I’ve seen so many movies at the New Beverly. It’s been so important to my life. These days I don’t go as often as I used to, but I still check in a couple times a year. Not too long ago I saw Reflections in a Golden Eye there. It’s a very interesting and very obscure film, directed by John Huston from a novel by Carson McCullers. I never expected to see it in a theatre, but the New Beverly ran it as part of a Marlon Brando retrospective. I was so happy to see it on the big screen. But it’s not just the programming that makes the New Beverly a special place. It’s special because it’s always been run by people who care about film.

Quentin Tarantino has provided support for the New Beverly for years, and actually bought the property when Sherman died in order to keep the theatre alive. I know it means a lot to him. But apparently there’s been a dispute going on about how the New Beverly should be run, and Tarantino has decided he wants to be in charge, effectively taking control of the theatre away from Michael. I just learned of this recently, and I’m not privy to all the details, so I suggest you follow the link below to hear the story from someone who’s been a witness. Ariel Schudson has been part of the New Beverly family for years. Here’s the post she wrote about the situation….

Honestly, I don’t know what to say about all this. I feel like a kid watching Mom and Dad argue. I don’t want to take sides, and the whole thing just makes me feel really awful.

It’s Such a Beautiful Day (2012)

Years ago I was with my family at Thanksgiving when my nephew told me he wanted me to see some stuff he’d found on the internet. We went upstairs, away from the rest of the relatives, and he showed me a series of cartoons that were incredibly creepy and hysterically funny, all of them by a guy named Don Hertzfeldt. I’ve never forgotten that day.

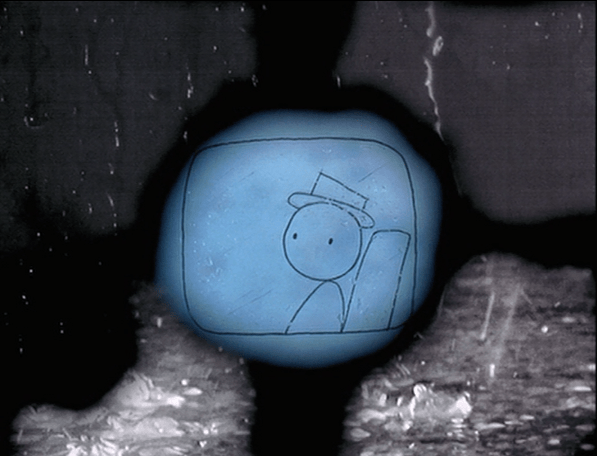

Hertzfeldt’s early work may have looked crude, but it was actually way more lively and interesting than most of the animation you see in theatres. The big studios spend millions on feature length cartoons with incredible technical polish and zero soul. Hertzfeldt creates his work himself, with his own hands. His simple line drawings are combined with found images that are often blurred and distorted. For his soundtracks he relies on ambient noise and a fair amount of shrieking. But the end result isn’t just funny, it’s disturbing and moving.

The early shorts are all about brutal, absurd situations where people often get hurt really badly. But in recent years Hertzfeldt has added other dimensions to his work. His most recent release, It’s Such a Beautiful Day, is an amazing piece of filmmaking. The crazy horror is still there, but now underlying it is a weird cosmic beauty. With all the terrible trauma we see on the screen, the film has a strange serenity to it. The universe may be a terrifying place, but Hertzfeldt accepts it as it is. And he seems to be saying that we should treasure the stray moments of happiness as they slip through our fingers.

You might think a film that was basically made by one guy would be a thin, minimal affair. But no. Hertzfeldt’s hand-made images vibrate with a crazy, implacable life. Flames leap across the screen. Seagull cries float on the breeze. Windows open up out of the darkness, flicker with distant memories and then close again. Along with the director’s deadpan narration, layers of sound create a dense, sometimes unnerving texture that can be overwhelming. A symphony orchestra plays while noise piles up on top of it, growing louder and louder until you just want it all to stop. And he also layers images over each other, in this case suggesting the way memories pile up in layers, rubbing against one another, slowly growing blurred and faded.

Memory is key in It’s Such a Beautiful Day. The film follows a man named Bill as he slowly falls apart, suffering from some unspecified disease. As his mind and body deteriorate, his memory fades. First he has trouble remembering recent events, and soon he can’t recognize people he’s known for years. Pictures from the past surface without warning, some that come from Bill’s distant memories, and others that conjure up frightening relatives who lived long before his time. The fear, pain and loneliness that haunt Bill aren’t new. They’ve been around forever, handed down from generation to generation.

This probably all sounds horribly depressing. Yeah. It is. Up to a point. But there’s that strange serenity I mentioned earlier. A sense of acceptance. It’s as if Hertzfeldt has stepped back far enough from our everyday struggles to take in the whole universe. Our suffering doesn’t seem so important in the vast, cosmic scheme of things. Bill’s final visions are of an eternal, shimmering, infinite universe in which he’s just a mote drifting through space.

Hertzfedlt may be an awful cynic, but there’s more to this movie than pain and loneliness. As Bill goes through his terrible downward spiral, he comes across reminders that people can care for each other, that tenderness exists. Love may be fleeting, but it is real. And finding the beauty in the world may just be a matter of opening your eyes to it.