Category Archives: Uncategorized

Down Time

As usual, I’m taking a winter break. While blogging can be fun, it can also be exhausting. I’ll probably start posting again around the end of January.

And once again, I’d like to give a shout out to the National Film Preservation Foundation. They’ve been responsible for restoring and preserving numerous films thought to be lost, and just this last year rescued the footage Orson Welles shot for Too Much Johnson. That alone would make me eternally grateful to the NFPF, but they’ve done so much more.

If you haven’t been to their web site, a link is below. And if you care about film, I urge you to consider making a donation.

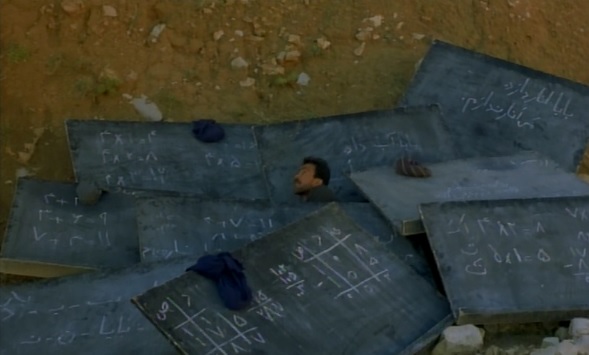

Blackboards (2000)

You won’t find Kurdistan on the map. But it’s very real to millions of Kurds. The region they live in has been battered by conflict for centuries, and the boundaries have shifted over and over again. After WWI Kurdistan was divided up among four neighboring countries, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Somehow the Kurds have managed to hang on to their culture and their language in spite of this. In some areas they’ve even gained a fair amount of political and economic clout. But there are also large numbers of Kurds who live as nomads, wandering through the countryside. This life has always been difficult. In recent years, with violence erupting all over the Middle East, it has become nearly impossible.

In her film Blackboards, Samira Makhmalbaf focusses on the Kurds who spend their lives travelling on foot through a harsh and desolate landscape. The story revolves around two teachers who are wandering across the mountains of Iran, hoping to find someone who will pay them for lessons. One runs across a group of boys who are smuggling contraband. The other falls in with a band of nomads who are lost in the wilderness. It turns out all of them are trying to cross the border into Iraq.

It’s clear these people lead hard lives, but those of us who have always had food on the table and a roof over our head probably can’t ever imagine how much suffering they’ve endured. Makhmalbaf slowly reveals pieces of their history, giving us glimpses of the violence they’ve been subjected to, but she’s not trying to win our sympathy. She’s not trying to bring tears to our eyes. Instead, she’s opening a window on the world these people live in.

Makhmalbaf somehow manages to combine rigorous objectivity with breathtaking poetry. She’s a born filmmaker.* She seems to have an intuitive understanding of sound and image. Blackboards is wonderfully simple. We follow two groups of people walking across a barren landscape, watching their faces, listening to them talk. The mountains and valleys that stretch across the horizon, dwarfing these frail travellers, have a stark, surreal quality. They seem both brutally harsh and strangely ethereal. Makhmalbaf uses music sparingly, and so much of the time these people are enveloped by an enormous silence, broken only by the sound of footsteps, scuffling across the dirt, clattering over stones.

The teachers are trying to sell their services, but nobody wants them. For people like this who are struggling just to survive, the idea of wasting time on luxuries like reading and writing seems pointless. An so the teachers, who start out aggressively, insisting that everybody needs what they’re offering, end up becoming beggars, following these desperate people, hoping to earn a piece of bread. At first the teachers can’t even get anyone to talk to them. Both the smugglers and the nomads are deeply suspicious of strangers. They have good reason to be. The boys make their living by acting as mules, carrying contraband across the border, trying not to get shot in the process. Having lived longer, the nomads have suffered more. They’ve persevered through years of conflict between Iran and Iraq, as well as two invasions by the US. The lone woman in the tribe is sullen and stoic. Even after marrying one of the teachers, she answers his questions in single syllables. Later we learn that she’s one of the few who survived when Saddam Hussein bombarded the city of Halabja with chemical weapons. She has no patience for useless talk. She’s too busy trying to make it through another day.

And that’s all the teachers are able to do. At the end of the film, they have nothing to show for their efforts. Border guards fire on the child smugglers, and the boys run for their lives. The nomads manage to cross into Iraq, but the teacher who was travelling with them chooses to stay behind. His divorce from his wife is as simple and quick as their marriage. And she walks off toward the horizon, carrying his blackboard with her.

*

The fact that she’s the daughter of Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf might have something to do with it. Maybe it’s just in her blood.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Nicolas Roeg’s early films are mysteries. He wasn’t really telling stories. He wasn’t creating drama. In the seventies and eighties Roeg was exploring a new language, melding sound and image, breaking down time and space. I always felt that understanding his films was less important than experiencing them.

That may sound like some kind of mystical rubbish, and there were plenty of people who accused Roeg of being glib and flashy. But from Performance (1970, co-directed with Donald Cammell) to Bad Timing (1980), I think Roeg was really trying to let us see and hear things in a new way. It may not have always worked, but I never doubted his sincerity.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is one of Roeg’s most ambitious films. It tells the story of the spectacular rise and fall of Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who comes to earth and builds a vast financial empire based on startling new technologies. The film was adapted from a novel by Walter Tevis. (Tevis also wrote The Hustler, which was brought to the screen by Robert Rossen in 1961.) While the narrative mostly moves forward, Roeg and screenwriter Paul Mayersberg don’t feel bound by traditional storytelling conventions. There are sensual reveries where bodies drift through an empty void. At times we hear sounds that seem to be echoing across the centuries. Time and space aren’t fixed in Roeg’s movies. They’re unstable. Porous. We may get a momentary flash of something that hasn’t happened yet. Or suddenly a window will open on the long lost past.

Mayersberg’s film résumé isn’t long, but it’s really interesting. In addition to The Man Who Fell to Earth, he also wrote Eureka for Roeg. And he wrote the screenplay for the 1998 film Croupier. It’s clear from just those three titles that Mayersberg is interested in outsiders. The first two are expansive, mythic stories of gifted men who build an empire and then see it stolen from them. The third in some ways is the polar opposite, focussing on a man who wants to isolate himself from the world around him, seeking safety in self-effacing anonymity. But all three are stories of individuals struggling with society, and in each one the main character finds himself trying to deal with a world which is basically corrupt.

Roeg is also interested in corruption, but tends to focus less on the world and more on the individual. His characters are often searching for something, sometimes literally on a journey of discovery. Along the way they tangle with sex and death, which in Roeg’s world are always closely intertwined. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, Thomas Jerome Newton seems to be immortal, but he watches everyone around him age, becoming weak and fragile. And while Newton has a wife and children back on his home planet, he’s not immune to desire. He meets a maid in a hotel and soon they’re sharing the same bed.

Sex is a subject Roeg is very interested in, and The Man Who Fell to Earth is more explicit than any other mainstream film I know of from the time. In your standard Hollywood film, sex is almost always about love, and it’s usually reserved for the main characters. That’s not the way it works in Roeg’s world. Love may or not may not be involved, and even when it is, the lovers are never pure. They’re just as vulnerable as real people, feeling loneliness, fear, insecurity and desperation. In his films sex is truly intimate, and that intimacy carries with it all the perils it does in real life.

I’ve seen the film several times, but this is the first time it occurred to me that the three principal talents, Roeg, Mayersberg and Bowie, are all British. Watching it from that perspective, it seemed to be very much about a foreigner slowly drowning in American culture. At first fascinated, then addicted, then overwhelmed and appalled. When Newton arrives at his hotel room in the Southwest, he asks Mary Lou to bring him a TV. Then more TVs crowd into the room. Finally he’s sitting in front of a wall of television sets, all tuned to different channels, bombarding him with chaotic visuals and disembodied voices. He’s confronted with a manic, kinetic collage of machines and animals, sex and savagery. The sensory onslaught becomes so overwhelming that he flips out. When he finally shouts, “Leave my mind alone!” is it just Newton shouting, or are the filmmakers also making a comment on the suffocating effect of American pop culture?

The visual texture of the film is wonderfully rich and extremely intricate. Anthony Richmond’s cinematography takes full advantage of Brian Eatwell’s stunning production design. As editor, Graeme Clifford gives it all a seductive, hypnotic rhythm. The sound is equally complex, thanks to the efforts of Robin Gregory, Bob Jones, Alan Bell and Colin Miller. It’s also important to mention the electronic effects by Desmond Briscoe, who pioneered the use of electronic sound in Britain. And the music is a fabulous crazy quilt of old standards, rock n’ roll, bluegrass and avant garde, to which John Phillips, Stomu Yamash’ta and Duncan Lamont all contributed.

As his career went on, Roeg moved toward a more conventional approach to image and sound. He seemed to be rejecting the oblique, enigmatic style of his early years and embracing a more straightforward kind of storytelling. That’s fine. As people mature, the obsessions of their youth often fall by the wayside. But I keep returning to Roeg’s early work, and I don’t think it’s just a sentimental attachment. There’s something in those movies that keeps calling me back. His films from that time are disturbing, sensual mysteries. Don’t try to understand them. Just let yourself fall into them.

To Catch a Thief (1955)

I’ve seen To Catch a Thief a number of times. At first I dismissed it as fluff, but I have to say it’s grown on me over the years. Even if it’s not up there with Hitchcock’s best, it’s still a pretty interesting piece of work. It was released in the mid-fifties, halfway through a decade in which the director made a remarkable series of movies, including Strangers on a Train, Rear Window, Vertigo and North by Northwest. During this period Hitchcock created some of his most complex, challenging films, and amazingly, he also enjoyed a long winning streak at the box office.

Like other directors who succeeded in Hollywood, Hitchcock understood that he was only able to hold on to his artistic freedom as long as he was able to produce money-making films. It was a balancing act. Sometimes he took chances, and his more daring projects didn’t always fare well at the box office. So he also made films that were calculated to please audiences, films that were conceived primarily as entertainment.

Which doesn’t mean to say that To Catch a Thief is completely superficial. One of the things that makes Hitchcock’s work so interesting is that he could deliver a film for the mass audience that was still subversive. Here he gives us the beautiful stars, the sumptuous sets and the stunning location work on the French Riviera, but at the same time he manages to pose some questions about the glamorous lifestyle that were seeing on the screen. He’s feeding us a slice of cake, but he also makes a point of asking if this is what we should be craving.

On the surface, the film’s tone is light and breezy, and John Michael Hayes’ script has a sharp wit that keeps us from taking it too seriously. The director is offering his audience a voyeuristic thrill by setting the film on the beautiful and luxurious French Riviera. Cary Grant plays John Robie, a gentleman jewel thief who’s gone straight. Grace Kelly plays Frances Stevens, a spoiled rich girl vactioning with her mother. Everything you need for a light, sophisticated thriller.

When I first watched To Catch a Thief, all I saw was the glittering surface. But on subsequent viewings, I started to catch interesting undercurrents. While Robie is a professional thief, the film makes the point that we’re all thieves in one way or another. Hughson, the straightlaced insurance agent who’s trying to recover the stolen jewels, gets uncomfortable when Robie calls him out on the fact that he’s padding his expense account. Hughson doesn’t like it either when one of his clients points out that selling insurance is basically gambling. And Frances, the headstrong heiress, wants to join Robie as a partner in crime, planning a robbery as though it was an amusing game. Throughout his career, Hitchcock kept reminding us that the line between law-abiding citizen and desperate criminal is very thin. The unfortunate heroine in Blackmail, the smug athlete in Strangers on a Train, the glib ad man in North by Northwest, all feel comfortably snug in their daily lives, until a twist of fate puts them on the wrong side of the law. The films may be fiction, but how many of us can say there hasn’t been a point in our lives when we could’ve crossed that line ourselves.

It’s redundant to call attention to Cary Grant’s striking skill and suave assurance. He’s pretty much perfect as the reformed thief. And I don’t want to spend a lot of time talking about Grace Kelly’s deft blend of cool wit and casual confidence. I’d rather focus on the supporting cast, which is just as impressive as the leading actors. John Williams made a career out of playing proper Brits, but here he gets a chance to have fun with the role. His drily understated performance is a joy to watch. Brigitte Auber has a strong and lively presence as Danielle, the amoral girl who wants to lure Grant back to a life of crime. But my favorite is Jessie Royce Landis as Frances’ down to earth mother. Landis was often cast as a matron, but in her films with Hitchcock she got to show how much she could bring to those roles. She does what the best character actors knew how to do, and that is to take a type and turn it into into an individual. In this film she gives one of the most enjoyable performances I’ve ever seen on the screen.

In making To Catch a Thief, Hitchcock was surrounded by an amazing team of collaborators. The film’s bright, crisp visual style was crafted by cinematographer Robert Burks working with art directors Hal Pereira and J. McMillan Johnson. Edith Head’s costumes add a layer of sumptuous style. George Tomasini worked as an editor on a number of Hitchcock films, all displaying a sharp sense of pace and rhythm. The only one of the director’s major collaborators from the fifties that’s missing is composer Bernard Herrman, but Lyn Murray’s score is enjoyable and energetic.

The Hollywood system has always demanded that filmmakers bring in the bucks. Hitchcock knew he had to balance his more personal projects with mainstream entertainment. But he also knew that these more conventional films could hold unconventional ideas. To Catch a Thief may appear to be nothing more than a slick, mainstream movie, but underneath the smooth, seductive surface, you’ll find that Hitchcock’s cold, hard intelligence is still at work.

Summer Vacation

I’ve been having too much fun to think about posting lately, so I’m taking the rest of July off. I’ll be back in August. Hope you’re enjoying your summer as much as I’m enjoying mine.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010)

Scott Pilgrim satirizes its subject at the same time that it’s giving it a big warm hug. The characters all live in a swirling pop culture universe where ordinary physical laws don’t apply. Characters move through three or four different settings in the course of the same conversation. Written words fly across the screen. Doors appear out of nowhere. And Wright pays as much attention to sound as he does images. He underscores the action by weaving together an intricate collage of ethereal voices, grating static and video game chimes. Most of it slides by without our being “consciously” aware of it, but Wright knows that it’s still having an impact. He understands how important sound is to the rhythm and the texture of a film.

When we first meet Scott, he’s an arrogant little jerk. Totally self-absorbed, he expects the world to revolve around him, and seems baffled when it doesn’t. Completely insecure, the smallest slight sends him into depression. But he meets a girl he really cares about, and she makes him raise his game. He realizes that if he’s going to be with her, he has to fight for her. It’s a standard coming of age story, but Wright tells it with a light touch and a wicked sense of humor. It may not be deep or heavy, but it is heartfelt.

Once more, we find Michael Cera playing a clueless nerd, and once more, he somehow makes the character interesting and engaging. He is truly obnoxious during the first part of the movie, but as he slowly, painfully starts learning what it means to take responsibility for his life, he starts to earn your respect. It helps that Cera has an amazing supporting cast to back him up. And Wright again deserves credit for the way he handles the actors. All the performances are stylized to fit the movie’s tone, but they’re not flattened out, as is so often the case when people try to make comic strip movies. All the characters are bursting with energy, and it’s hard to single anybody out because they’re all so enjoyable to watch. Kieran Culkin is razor sharp as Scott’s gay roommate Wallace. Ellen Wong somehow manages to make a character named Knives believable, first as an absurdly innocent schoolgirl, and then as Scott’s insanely jealous ex-girlfriend. As Gideon, Ramona’s rock producer ex-boyfriend, Jason Schwartzman is so unctuously hip that you want to punch him. He’s great. And while everyone else is freaking out or falling apart, Mary Elizabeth Winstead brings a low-key vibe to the part of Ramona, sort of like the calm at the center of the storm. She has a matter-of-fact openness that stands in stark contrast to Scott’s raging insecurity. You can see why he’s drawn to her, and also why she’s such a huge challenge for him.

Scott Pilgrim tanked at the box office. According to the IMDB it only earned thirty million in its US release, but most of the people I know who saw the movie loved it. I wouldn’t be surprised if in five years or so it’s considered a cult classic. It’s probably not for everybody, and no doubt plays better with younger viewers. But it is a legitimately awesome flick. It seems like most of the comedies that get released these days are competing to gross us out. What a welcome surprise to see a smart, stylish comedy that relies on wit and imagination.

If only we could clone Edgar Wright.

Support the Independents

On Saturday night I went out to the Nuart to see John Sayles’ new movie, Go for Sisters. It’s a moving story about a mother who goes to Mexico looking for her kidnapped son. She’s accompanied by a friend, a former addict who’s trying to get back on track, and the two of them join up with a former cop who helps them navigate the streets of Tijuana. As you would expect with Sayles, the screenplay is excellent, and the performances by LisaGay Hamilton, Yolonda Ross and Edward James Olmos are first rate. It’s a tough, tense little movie that really digs into the characters.

Sayles has been around since the seventies, shunning the bright lights and big bucks of Hollywood in order to do things his own way. He has doggedly pursued his goal of making honest movies, and as most independent filmmakers will tell you, this is always an uphill battle. After the movie was over, Sayles was joined by Hamilton and Olmos to take questions from the audience. During the session, Hamilton asked the audience to help get the word out, and that’s the reason for this post.

Go for Sisters is getting very limited distribution, and the filmmakers have very little money to promote their work. They need our support. They deserve our support. The link below will take you to the web site, where you can view a list of dates and locations. If you want to see a real movie about real people, check it out.

My Own Private Idaho (1991)

The first image we see in My Own Private Idaho is a young guy standing by a lonely road waiting for a ride. We hear crickets chirping. Birds chattering. The landscape is huge and beautiful and rolls all the way back to the horizon where it meets the sky. The guy, Mike, starts speaking to no one in particular. He talks about how he recognizes this road. He’s been on it before. He says it looks like a fucked-up face. Then he starts to tremble, and within seconds he has fallen down in the middle of the road, fast asleep.

Mike is a narcoleptic, which means he can fall asleep at any time with little warning. He’s also a hustler. He wanders around the northwest, hitting the cities, turning tricks at night and hanging out with friends during the day. Obviously, it could cause problems for a hustler if he’s prone to passing out when he’s with a client. At one point he has a seizure when he’s with an older woman. It seems she reminds him of his mother….

This rootless wanderer, a hustler in search of a home, is at the center of My Own Private Idaho. Mike is the classic Van Sant character. He wants to connect with the people around him, but he’s too innocent and too fragile to play their games. He sells his body for money, but he doesn’t know the facts of life. Van Sant builds this complex, rambling film around a young man who’s searching for some kind of perfect love. Mike hangs out with the hustlers in Portland, rides a motorcycle to see his brother in Idaho, and even takes a plane to Italy looking for that warm, nurturing embrace. But he’s looking for love in all the wrong places. He’s chasing a fantasy that only exists in his mind.

Mike thinks about his mom a lot. He has visions of her holding him, speaking to him softly, reassuring him. In his memory she’s an idealized figure, gentle, sweet, loving. From what we learn about Mike’s childhood, though, it was anything but ideal. Apparently his mother spent some time in an institution. He hasn’t seen her for years. Throughout the film Mike talks about wanting a home, a family. He feels lonely and lost. Really he just wants to be loved. Unfortunately, he ends up falling in love with Scott.

Scott is also a hustler, but not because he needs the money. His dad is a bigshot in Portland. The family is loaded. Scott could be living in the lap of luxury, but he likes living on the street, drifting around, doing drugs and pulling petty scams. He also likes the fact that his lifestyle is a slap in the face to his father’s straight world. When a city official shows up with a legion of cops to fetch the wayward youth home, Scott pretends to be having sex with Mike. He just wants to see the embarrassed looks on the squares’ faces. Scott revels in the crazy, messy world of the misfits who scrape to get by on the streets of Portland. He especially enjoys the company of an aging vagabond named Bob Pigeon, who he calls his true father. But this lowlife prince knows he’s slumming. He knows that in the end he’ll cut Bob loose, along with all his other hustler friends.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because Van Sant has lifted this part of the story from Shakespeare’s Henry IV. But there’s another layer here, because the relationship between Scott and Bob is actually based on Orson Welles’ adaptation of the play, Chimes at Midnight. Welles’ film essentially follows the structure of Henry IV, but there is a major change in emphasis. Where Shakespeare focussed on the prince’s transformation from roustabout to ruler, Welles’ drama is about the prince’s betrayal of his best friend, his “true father”, Falstaff. And this is the heart of Van Sant’s film, too. Mike and Bob both love Scott. They’re innocent enough to believe that he loves them, too. And he does, but only up to a point. When the time comes for him to take over his father’s role, he does it without hesitating. And there’s no place for his old friends in his new world.

There’s another thread running through the film, so subtle that it’s almost subliminal until the very end. A few of the characters, including Mike’s mother and brother, are seen wearing crosses. At first I wondered what this was about, because I couldn’t see anything explicitly Christian about the movie. But it all becomes clear at the funeral for Scott’s father. We see a group of people gathered in a cemetery, everyone dressed in their Sunday best, and the minister reading from the Gospel. “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal.” There’s an accordion playing softly in the background, but it’s not part of the service for Scott’s father. We see that another funeral is taking place just a few hundred feet away, or maybe not so much a funeral as a wake. A group of Scott’s former friends are gathered around Bob’s casket, getting ready to lay him to rest. Their gathering starts out quietly, but soon becomes loud and raucous, with everybody screaming Bob’s name. The formal service for Scott’s rich father, one of those who laid up his treasures on earth, is dull, dreary, dead. The mad gathering to mourn Bob is made up of misfits and outcasts, loners and losers. The people Christ spoke for.

Van Sant knew exactly what he was doing when he cast River Phoenix as Mike, the young, clueless, drifter hustler. He seems to just be living in the moment, a pretty boy with innocent eyes, hanging on a street corner, waiting for a trick or a friend to come along. Keanu Reeves is excellent as Scott, a suave, smug rich kid who knows from the start that he’ll eventually cut all these people loose. And then there’s the great Udo Kier. As Hans he has an awkward charm, a winsome vulnerability, and he provides some of the film’s best comic moments. Kier is in a category all by himself. There’s no one else like him.

My Own Private Idaho has so many different layers that it’s hard to grasp them all. I get the sense that this was a very personal project for Van Sant, and that he poured everything he was thinking and feeling into it. It’s not a neat, tidy, linear film. It’s a sprawling, rambling epic. A poem in sounds and images. Van Sant shows us hustlers hanging in coffee shops, houses falling out of the sky, and the vast grandeur of the American northwest. The soundtrack is a lovely patchwork that weaves together America, the Beautiful, music from the Renaissance, and the Pogues. It also includes original material by Bill Stafford that echoes the melancholy beauty of decaying hotels and lonely roads. Van Sant is trying to say a lot in this film, and I really don’t care if it all fits together. This isn’t a movie you understand with your head. It’s a movie you feel in your heart.

Eve’s Bayou (1997)

A lot of movies have been made about families, but not many honest ones. Most of the time, even if the film digs into some of the more difficult issues that arise between husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, everything is resolved before the fade out. We may see anger, envy, cruelty, betrayal, but generally speaking it’s all explained away by the end of the story. Everybody has their reasons, everybody has their issues, and everybody ends up burying their problems to join in a big, warm group hug before the final fade-out.

And so a film that really examines the toll that lies, jealousy, desire take on a family is rare. Eve’s Bayou deals with all those things, bringing us into the world of a prosperous Southern family, gradually revealing the dynamics that both keep them together and tear them apart. And in spite of the brutal emotional conflicts, the overwhelming sadness, the film is infused with a radiant beauty. This movie is not about despair. It’s about life.

Like The Magnificent Ambersons, Eve’s Bayou isn’t just about a family, it’s about where they live. Writer/director Kasi Lemmons opens the film by telling us that the bayou was named after a slave who was freed by her master. She then bore him sixteen children. Their descendants, the Batistes, are the focus of the story. Their large, comfortable home is at the center of the film, but Lemmons also takes the time to show us the town, its people, its market, its cemetery. The family is well-respected, and proud of their standing in the community. In fact the father, Louis, is more than proud. He’s arrogant, cocky, and his brash confidence will be his undoing.

Another thing the film has in common with The Magnificent Ambersons is the way the director uses a party to bring us into the world of this family and to lay out the relationships. After a brief prologue, we find ourselves in the bayou at night, drifting across the dark water, floating past the heavy trees until we find ourselves in front of the brightly lit Batiste home. Inside there’s music playing, people are dancing, and everybody seems to be having a great time. But Lemmons gradually takes us deeper, allowing us to catch the careless gestures, the whispered gossip, the hurt glances that nobody notices. And before the end of the party, the main character, a young girl who worships her father, has had her eyes opened to an ugly truth that shakes her to the core.

This is the moment that sets everything else in motion. The realization by Eve that her father is not the hero she thought. She shares the secret with her older sister, Cisely, who is shocked at first, and then insists that nothing happened. Cisely tells Eve she just imagined it. That there’s nothing to worry about. Which is what children often do when confronted with their parents’ sins. You have to bury the knowledge, forget about it, go on as if nothing happened. And then maybe spend years or decades trying to keep the memory from rising back to the surface.

Starting with the opening shots of the bayou, Lemmons gradually draws us into the life of this small Southern town. She seems to favor long takes, slow tracking shots, allowing us to drink in the serenity and stillness of this melancholy world. The sunlight undulates slowly across the dark, smooth water of the bayou. The dense, green foliage seems to embrace life and death at the same time. In the audio commentary we hear Lemmons talk about her close collaboration with cinematographer Amy Vincent and editor Terilyn Shropshire. I was especially interested in what they had to say about finding “organic” solutions, which I took to mean finding simple, direct ways of expressing the story’s themes. Terence Blanchard’s score also plays a crucial role. His subtle orchestral textures, complemented by harmonica and guitar, perfectly match the emotional tone of the film.

As visually rich as the movie is, it wouldn’t mean a thing if the actors didn’t deliver. But not only does Lemmons get great performances out of the individual cast members, they work beautifully as an ensemble, making us believe that they’ve known each other all their lives. Samuel Jackson is smoothly confident as the philandering father who gets offended when anyone questions why he’s never home. Lynn Whitfield plays the beautiful, loving wife, who struggles to raise her children while the knowledge that her husband is cheating eats away at her. Meagan Good has all the poise and authority of a confident, radiant older sister who knows she’s her father’s favorite.

And at the center of the movie is Jurnee Smollett as Eve. It’s one of the most remarkable performances I’ve ever seen a young actor give. She has all the trusting sweetness and all the bitter anger of a girl on the verge of adolescence. Her mood changes in an instant, projecting smug confidence one minute and absolute despair the next. She’s full of love and hate at the same time, torn apart by emotions she doesn’t even understand. Lemmons says she spent a long time looking for a girl to play Eve, but on seeing Smollett immediately knew she was perfect for the role. It’s hard to imagine anyone else in the part.

Eve’s Bayou is one of the few movies that really captures families as they are, diving deep into the currents of love and jealousy, bitterness and loyalty that bear mothers and fathers, sons and daughters relentlessly forward. It doesn’t tell us that everything’s going to be all right. All of this will go on forever, and all of this will fade into the past.

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971)

This is a movie made by guys about guys. James Taylor and Dennis Wilson play two gearheads whose lives revolve around their car. We never get to know their names, and the credits just list them as The Driver and The Mechanic. Warren Oates is an amiable eccentric who picks up hitchhikers in his yellow GTO. The three meet on the road and bet their pink slips on a cross-country race. For the rest of the film we follow them as they travel down country highways, stopping at diners or garages, racing to make a few bucks when they need to.

It’s that simple. This movie discards all the conventions we expect from commercial films. It’s not played for suspense or for laughs. There’s no love story. We just follow these guys as they drive across the country. The lone woman in the film is a hitchhiker who joins the group early on. Played by Laurie Bird, the character is only identified as The Girl, and like the other three she seems to be drifting aimlessly.

Two-Lane Blacktop is a road movie in the purest sense of the word. Director Monte Hellman decided to shoot the movie on location and in sequence, and so the crew spent weeks travelling across the US, shooting on country back roads and in small towns. Though the film plays out against the backdrop of the vast American landscape, it’s actually very intimate. It’s a portrait of three guys, and in spite of their obvious differences, they’re all united in their obsessive urge to keep moving. Through car windows we see lush forests and grassy fields sliding past. We ride through endless, dusty plains, under blue skies filled with tiny cloud tufts trailing off to the horizon. The small towns that appear now and again seem to be nothing more than a few buildings gathered along a stretch of road. Hellman and cinematographer Jack Deerson give us a detailed panorama of rural America. They capture the cities and the towns and the forests and the hills, but just as important, they also capture the spaces in between.

The film also takes advantage of another kind of space, and that’s the “silence” between lines of dialogue. I put the word in quotes, because it’s not really silence that we’re hearing. Actually, we’re listening to the sounds that most movies push into the background. The clatter of dishes in a coffee shop. The murmur of conversation in a bar. The drizzle of rain falling in a tiny rural town.

The film seems to catch life as it’s happening. The performances are so natural and unforced that they appear to be improvised, though the director says he followed Rudy Wurlitzer’s script closely. According to Hellman, there are only two scenes that stray from what was written. The Driver and The Mechanic speak very little to each other, and when they do it’s almost all about cars. How the engine is running, how the car is handling, where they can make repairs. At the opposite end of the scale is GTO, who loves to hear the sound of his own voice. None of the three, though, says much about what they’re feeling. A crucial exception is the brief scene when GTO seems to open up and start talking about how his family is falling apart. The Driver quickly shuts him down. No need to hear about each others’ problems. There may be a world of pain inside each one of these guys, but it’s better not to talk about it. Just keep driving.

*

I went out of my way to see Two-Lane Blacktop at the Aero in Santa Monica. I had seen it once before years ago at the New Beverly, and wanted to watch it again on the big screen. Monte Hellman was there and after the screening he talked about the movie. It was interesting to hear his comments on the making of the film, and it was also interesting to hear him talk about this particular screening.

The credits list the authors of the screenplay as Will Corry and Rudy Wurlitzer. According to Hellman, he gave Corry’s original script to Wurlitzer, who said he couldn’t get through more than a few pages. Hellman says he then told Wurlitzer to go ahead and write what he wanted, and that all they used from Corry’s version is the concept of two guys in a car.

Hellman went on to say that the film bombed at the box office, which he blames on lack of support from Universal. Apparently Lew Wasserman, who ran the studio back then, saw the movie and hated it. So while Two-Lane Blacktop was shown at theatres nationwide, Universal did nothing to promote it. Aside from a rave review in Esquire, the critics were not enthusiastic. But over the years it has gained a sizable audience.

One of the audience members said he had last seen the film at a drive-in when it first came out. Hellman at first responded enthusiastically, and said that’s the way it should be seen, on a huge screen. But then he talked about the print we had just watched and said that the colors were not as rich as they had been in the original dye transfer prints. I was kind of stunned when he went on to say that these days he preferred to watch the film on Blu-ray, because the image was crisper and the sound was richer.

But I’m still glad I saw it on the big screen.